Getting To Know The Fungus Among Us (In Our Guts)

12:06 minutes

Your gut microbiome is composed of more than bacteria—a less populous, but still important, resident is fungi. Many people’s lower digestive tract is home to the yeast Candida albicans, the species implicated in vaginal yeast infections and oral thrush. But new research published in the scientific journal Nature this month suggests that Candida in the gut may also be related to severe cases of inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD.

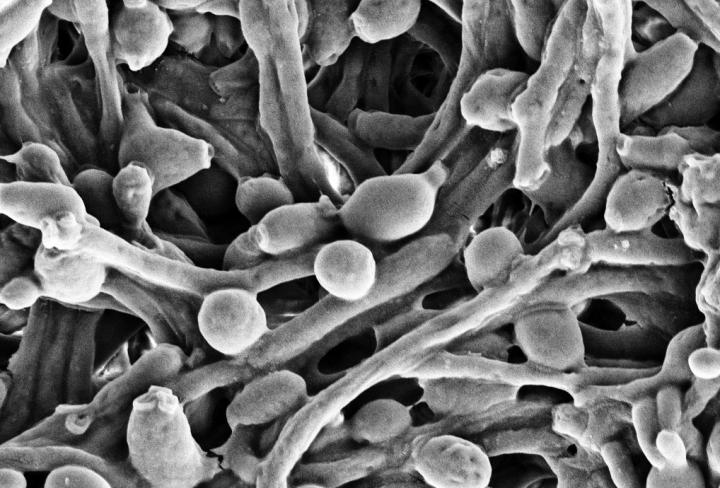

Candida comes in multiple forms: a single-celled, rounded yeast, and a multicellular, branched version, known as the hyphal form. The latter is capable of invading other cells, and is associated with tissue damage, like that of IBD. The research team writes that our immune system reacts to candida by targeting a protein found on that second, invasive state. Conversely, our bodies seem to leave the rounded, yeast form alone.

Better understanding what drives these distinct responses may provide clues to developing a vaccine that could help people with candida-linked health problems. And postdoctoral researcher Kyla Ost tells guest host Roxanne Khamsi that the relationship appears to be mutualistic—that is, the fungi themselves benefit from being managed in this way.

She explains the nuanced relationship she and her colleagues uncovered, and how uncovering more about gut fungi may bring new insights into the relationship between our microbial communities and our health.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Kyla Ost is a postdoctoral researcher in Pathology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: This is Science Friday. I’m Roxanne Khamsi. Ira is away this week. Later in the hour, we’ll talk about how science has a starring role at this year’s Olympics. Plus, new research into earthquakes on Mars, though I suppose we’d better call them Mars-quakes.

But first, longtime listeners will know that the human gut microbiome is a favorite subject of this show. We’re learning more every year about how communities of bacteria, viruses, and fungi operate in and on your body to both harm and benefit your health. And yes, you heard that right, fungi are part of that equation.

And just as the community dynamics of the bacteria in our gut may have a role in our health, researchers finding interesting relationships between our immune system, fungi, and conditions like inflammatory bowel disease. Kyla Ost is a Postdoctoral Researcher in Pathology at the University of Utah and a co-author of new research on a fungus called Candida albicans. Welcome, Kyla.

KYLA OST: Thank you, Roxanne. I’m excited to be here.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: Can you tell me a bit about which fungi are there and what they’re up to? I mean, we’re not talking about full-fledged mushrooms, for example, right?

KYLA OST: You’re exactly right. When we think of the gut microbial community, your mind automatically goes to the bacteria, which, in all fairness, make up the vast majority of the microbial community. But among this complex community of microbes, there are fungal species. And, of course, like you said, these are not mushroom species. They are yeast species, typically.

And so what’s a yeast? A yeast is a single-celled organism that grows typically in little circular buds. And under a microscope, they look very similar to the yeast that you think of that makes our beer and you use to make bread. These single-celled yeast species, while they are vastly outnumbered by the bacteria within the gut, are really important for host health.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: And the species you’re looking at specifically is Candida albicans, right? What is Candida up to?

KYLA OST: Yeah. So Candida albicans is typically the most dominant or abundant fungal species in a human gut. Most of what we know about Candida is from its pathogenic potential. So we know that Candida is a normal colonizer of the human gut.

But in people who have compromised immune systems, the Candida can overgrow and invade host tissues to cause infections like thrush or vaginal yeast infections. But recent research has demonstrated that Candida albicans and other Candida fungi can exacerbate inflammatory diseases like inflammatory bowel disease. And that is the sort of disease that we focused on in this study.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: And you and your colleagues found that whether Candida albicans is harmful actually depends on what shape it took?

KYLA OST: Yeah, you’re exactly right. So Candida and other fungi, in fact, are really fascinating because they’re shapeshifters. And Candida albicans is really famous for undergoing this morphological transition from growing as a single-cell budded yeast to an elongated multicellular hyphal form. And this is really important because the hyphal form of Candida is more pathogenic, so it’s better at adhering to host tissues and invading host tissues.

Basically, what we found was that our immune system is really good at targeting and suppressing this hyphal pathogenic form of Candida. And we further showed that this hyphal form of Candida is much more pathogenic in a mouse model of IBD than the yeast form. And so the implication of our work is that, potentially, it’s not necessarily just the presence of Candida albicans within the gut that is exacerbating disease, but it’s the form that that Candida albicans has taken that may be important for disease exacerbation.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: Yeah. It’s like a lot of shapeshifting going on with this Candida albicans. I didn’t imagine all this stuff was happening in our guts. So what is our immune system doing to target that sticky type of Candida albicans?

KYLA OST: What we found was that it’s actually antibodies that appear to be specifically targeting this hyphal form and suppressing the hyphae within the gut. And so antibodies are immune molecules designed to target molecules often on pathogenic microbes. And in the gut, it’s actually quite fascinating because our gut immune cells make a lot of antibodies every day, even in the absence of infection.

And these microbes within our gut, including Candida albicans and other commensal species, sort of live their whole lives in a environment teeming with these immune molecules that are constantly targeting them. And so, yes, what we found is that these antibody responses are really important for targeting and shaping the Candida albicans’ biology in such a way to suppress hyphae and pathogenic molecules on these fungi to potentially suppress their pathogenic potential.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: Can you kind of connect all this with the inflammatory bowel disease, this really common gut disorder?

KYLA OST: So what our study is focused on is trying to understand how Candida albicans is maintained in a non-pathogenic state in a sort of a healthy situation. And so the antibody responses that we found were not sort of specific or different, depending on IBD status, but I want to emphasize that they were present in healthy people along with people with IBD.

And so what we think this represents is a normal sort of homeostatic interaction between antibody responses and this commensal yeast that most of us carry around within the gut that actually promotes its commensalism. By that, I mean prevents pathogenic Candida from arising.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: Does the yeast form of Candida albicans actually help us in any way? Why would our immune systems leave it alone when it’s in that kind of friendly form?

KYLA OST: That’s a fantastic question, one that I and many others in the field are trying to answer, but I would say that there have been a number of really fascinating recent studies to suggest that Candida albicans in the gut may serve a beneficial purpose, that it might be beneficial in some way. And particularly, Candida albicans is pretty immunogenic, so it’s really good at getting in your gut and inducing strong immune responses without leaving the gut, so living in its normal commensal place.

And researchers have recently found that these immune response induced by Candida can protect potentially from other pathogenic microbes like bacteria. So there have been some clues to suggest that Candida in the gut may be beneficial. But, yes, you’re right, it depends on sort of the biology or maybe even you could think of the behavior of the Candida in the gut, whether it has beneficially– a beneficial potential or pathogenic potential.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: So usually, we have this picture of the immune system coming in to save us from invaders, but it sounds like what’s going on with these fungi is a little bit more nuanced. Can you unpack that a bit?

KYLA OST: Oh, I’m so happy you picked up on that. That’s the bit about our study that fascinates me the most. You’re exactly right that there’s a complex and not very– it’s not necessarily linear sort of interaction between our immune system and fungi or Candida albicans in the gut. What we found, ultimately, is that these antibody responses are really good at targeting Candida albicans, but, in fact, they’re not responsible for clearing or suppressing the total level of Candida within the gut.

Instead, what appears to be happening is that these antibody responses are altering or sculpting the biology of the Candida population within your gut to suppress the sort of bad form of Candida within the gut. And the fascinating bit about this is that we discovered that Candida albicans itself appears to gain a fitness advantage from this immune sculpting.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: Oh, my goodness.

KYLA OST: What that means is that the selection for these yeast cell types over the hyphae improves Candida’s fitness for gut colonization. Other studies have demonstrated that the yeast cell form of Candida for some reason does a whole lot better in the gut than hyphae. And our study demonstrates that antibodies may be helping Candida basically be the best commensal it can be while also preventing sort of the damage that Candida could potentially cause.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: I mean, that’s definitely a two-way street between our immune systems and the Candida albicans, it sounds like.

KYLA OST: I like to think of it as a communication, that the Candida and the host are sort of moving towards a mutualistic interaction to maintain homeostasis.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: So we’ve talked a little bit about how this relationship can go wrong sometimes. And I know that in those situations, we have antifungals, but there’s also rising antifungal resistance. So this antibody response to Candida albicans that you found, can we use that somehow and harness it to make the disease less severe for people?

KYLA OST: Yes, that’s exactly what we tested and what we think we’ve shown. We used a Candida albicans vaccine which has been developed originally to prevent Candida albicans infections. And this vaccine is fascinating because it is– it’s called the NDV-3A vaccine. It’s designed to target just one type of adhesion molecule, a sticky molecule, on Candida albicans that we found was also a target of these intestinal antibody responses.

And so what we found was that this adhesion-based vaccine was really effective at preventing Candida from aggravating IBD in mice and suggests that this vaccination strategy could be a potentially useful therapeutic to prevent this type of pathogenic interaction with Candida in people.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: This is fascinating, I have to say. We’re all walking around with these communities of fungi and bacteria in our guts. And so I am curious still to know a little bit more about are there any questions you have about how your immune system is interacting beyond what we already? Is there anything you’re dying to know about the immune system’s relationship with all these living organisms inside of us?

KYLA OST: Yes. It is, I have to admit, something I think about all the time. I think there’s many really important questions that we still don’t understand about sort of immune responses and microbes. When we think of these antibody responses, we think of it being very linear, in which the microbes induce the response, the response targets them and clears them.

But now we’re really understanding is that the commensal microbes within our gut are inducing these immune responses throughout our life, and we carry them throughout our life. And so what interests me is understanding how microbes– not just the commensal microbes, but also pathogens– contend with this mature immune environment that is always present and always changing. We don’t know that much about how this immune environment sort of shapes the biology and the interactions of the host of different microbes.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: Well, I have to say, I’m really going to be thinking about all of this, and especially my immune system, the next time I have a meal. So thank you, Kyla. That’s all the time we have, but we really appreciate your joining us today.

KYLA OST: Thank you so much.

ROXANNE KHAMSI: Kyla Ost, Postdoctoral Researcher in Pathology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.