White House Declares Monkeypox Outbreak A Public Health Emergency

12:15 minutes

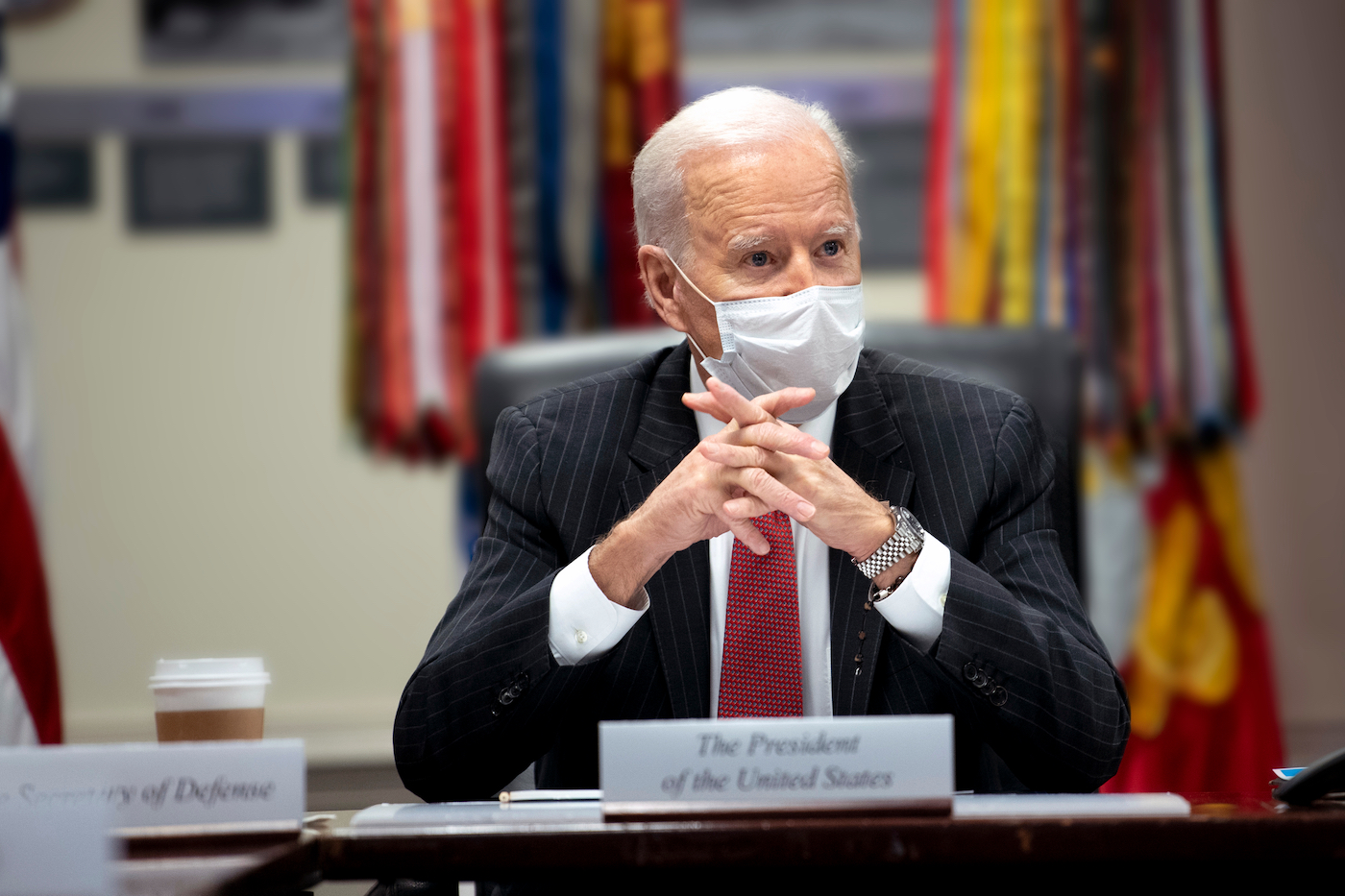

The Biden administration declared the monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency on Thursday.

Earlier in the week the White House appointed Robert Fenton, regional administrator at FEMA to direct the federal government’s response to the monkeypox outbreak, along with a deputy director from the CDC.

This comes after criticism from activists and public health experts, who have said that the federal government has been dragging its feet on access to vaccines, testing and treatment for the virus.

Ira talks with Tim Revell, deputy United States editor for New Scientist, about the latest monkeypox updates and other top science stories including; new research into the shape of the human brain; how hand gestures can improve zoom calls and a plant that harnesses the power of a raindrop to gulp down insects.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Tim Revell is Executive Editor at New Scientist in London, England.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, working on a vaccine for cancer, how recent advances in our understanding of the immune system are opening the door to new types of cancer therapies.

But first, the latest on monkeypox. On Thursday, the Biden administration declared the monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency. And earlier in the week, the White House appointed Robert Fenton, regional administrator at FEMA, to direct the federal government’s response to the monkeypox outbreak, along with the deputy director from the CDC.

This comes after criticism from activists and public health experts who said that the federal government had been dragging its feet on access to vaccines, testing, and treatment for the virus. Joining me now to give us the latest monkeypox updates and other top science stories of the week is Tim Revell, deputy US editor for New Scientist. He’s based in New York. Welcome back to Science Friday.

TIM REVELL: Hello, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: And now that the White House declared monkeypox a public health emergency, what exactly does that mean? What opens up now?

TIM REVELL: Yeah, so this had been coming for a few weeks now. I mean, if you recall that the World Health Organization declared monkeypox a public health emergency almost two weeks ago now, and then there had been quite a lot of calls for the US to do this as a national emergency, and then a few states like New York, California, and Illinois declared states of emergency for monkeypox. So the idea is that by declaring a national health emergency, that frees up some funding and resources to tackle the problem.

So that includes things like extending the group of people who can administer vaccines such as emergency responders, pharmacists, and midwives. And it also gives the FDA more power. So part of that is being able to skip parts of its exhaustive review process to authorize measures for diagnosing, preventing, and treating monkeypox. And that was actually used quite a lot during the coronavirus pandemic. And there’s talk that this power could perhaps make it possible to drastically increase the number of monkeypox vaccine doses that are available in the US without actually making any more vaccines.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. There have been reports that the vaccines are hard to come by. Where are we now with this?

TIM REVELL: Yeah, so the vaccine that’s approved by the FDA for use in the US, it’s called JYNNEOS. And it’s produced by a company in Denmark called Bavarian Nordic. And it’s supposed to be that you get that with two doses, 28 days apart. And it’s very good. It can prevent someone from getting the disease completely. And it can also alleviate symptoms if you’ve already had it.

So federal officials think that there’s about 1.6 million people in the US at the highest risk of monkeypox, of catching monkeypox. But they only currently have around enough doses for 550,000 vaccinations. So here’s where that additional FDA power could come in. So at the press conference yesterday, there was talk of a plan where you might be able to get five doses from a single vial of the JYNNEOS vaccine.

And this is called dose sparing. And in this situation, it would work by using a shallower injection than would typically be used to administer the dose. And there’s a study from 2015 that suggests that doing that, you can use less of the vaccine, but you get the same amount of immune response. And that plan could be finalized in the next few days.

IRA FLATOW: That’s really interesting. So who is eligible to get the vaccine? Should we all be anticipating the need for a monkeypox vaccine, like just like we did for COVID?

TIM REVELL: Yeah, not yet. So primarily, monkeypox is spreading in men who have sex with other men. And that’s around 99% of cases. So at the moment, that’s the primary group that’s being targeted for vaccinations. So people who have sexual relationships with other men and who are at high risk, for example, people who have disorders that give you a compromised immune system, such as HIV, are being particularly encouraged to come forward.

The difficulty at the moment is actually getting hold of the vaccine is quite difficult. In New York, there has been instances where people have tried to get vaccines, and the system’s been all booked up, or there’s been a glitch. Currently, the advice is that vaccine appointments are booked up for the rest of the month. But if you’re in one of the groups that’s being asked to come forward, that you should keep checking the website, and hopefully a cancellation will lead to free appointments. So it’s a bit difficult, and it’s moving quickly at the moment.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I want to tell our listeners that if they have questions about monkeypox or misinformation floating around that you want us to debunk, send us your questions, and we’ll get them answered by a monkeypox expert on the show next week. And you can do that by sending us a voice memo, SciFri at sciencefriday.com, SciFri at sciencefriday.com, or find us on Facebook or Twitter.

Let’s move on to our next story. It’s one of these “science marches on” kinds of stories, where new research shows that the shape of the human brain actually hasn’t changed much in the past, what, 160,000 years. That goes against all the theories we know.

TIM REVELL: Yeah, absolutely. So we know the skull has changed in that time. Since early modern humans first arrived on the scene around 200,000 years ago, the actual size of our craniums hasn’t actually changed that much, but the shape has. And we thought this was due to the brain. We thought what had happened is that behavior changes, such as the development of tools and art, had meant that our brains had become rounder. And as such, that made our skulls a bit rounder, too.

However, that’s where this new research comes in, suggesting that that could be all wrong. So this was a story that Luke Taylor did for us at New Scientist, and it’s how researchers at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, they analyzed and compared hundreds of ancient human skulls. And they found that the size and proportions of the skulls of Homo sapiens children from around 160,000 years ago were pretty much the same as children today, but the adults were very different.

And so as the brain reaches about 95% of its adult size by age six, that suggests that it’s actually not the brain that’s causing those differences, as they come much later. So this does raise the question if it’s not the brain changing our skulls, what did change our skulls over that period of time?

IRA FLATOW: Huh, very interesting. And speaking of really interesting, we recently experienced the shortest day on Earth since the 1960s. Is the Earth spinning faster?

TIM REVELL: Yeah, I don’t know if you noticed, but at the end of June, we had a day that was our shortest day since the 1960s. And it was 1.59 milliseconds sooner than expected. And so there’s a really fun story from Ian Sample at the Guardian. And we’ve actually seen quite a few records fall of late. So in 2020, we had 28 of the shortest days in the past 50 years, which I don’t know about you, but I actually had the complete opposite feeling in 2020.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS] Yeah, they were not forever.

TIM REVELL: Yeah, this would make you think maybe it’s the Earth’s spin. It’s starting to spin more quickly, is that’s what’s going on. But actually, it’s doing the opposite. So if you sort of look back in deep time over the last billion years or so, a day would pass in less than 19 hours. And then it’s been slowly increasing on average since then.

So what caused these little records that we’ve seen over the last 50 years, which is such a minute period of time compared to deep geological time, is all the little variations that we get on Earth, so things like the molten core sloshing about, the way the oceans move, earthquakes, and tsunamis, can all affect exactly how quickly Earth is spinning. And that can cause these tiny little fluctuations day to day.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, that is really cool. Who knows? It might get longer one of these days.

TIM REVELL: Yeah, well, that will almost certainly happen. We’ll have it slightly longer. But it will only be for a very brief period.

IRA FLATOW: I want to end on some breaking news in the carnivorous plant world. Scientists have shown how pitcher plants are able to launch insects into their pouches using the power of raindrops. You’re going to have to tell me how that works.

TIM REVELL: Yeah, hot off the plant press. You’ve probably seen these plants before. So picture plants, they’re these carnivorous plants from Southeast Asia. And they have these sort of specialized leaves that look like elongated sacs with digestive fluid at the bottom. And so inside these sacs is a nectar which attracts insects and a sort of slippery wax that normally sends the critters tumbling down to their doom.

But there’s a second mechanism that we’re now learning more about, which is that these elongated sacs, they also have a little lid on top. And sometimes insects crawl on the underside of the lid. And really, if you’re a pitcher plant, you want a way to fling those insects into your digestive pool, so you can eat them as a snack.

And it turns out the way that they do this, which we’re now learning more about, is that as raindrops land on the top, they have a sort of elasticated part towards the back that stores elastic energy. And then it can use that to really catapult an insect.

And it’s a very similar mechanism to when you get several people on a trampoline all at once. And if they bounce at the right time, it causes the person in the middle to really launch in the air much higher. And it’s that same principle at play here, where you can fling an ant into the digestive pool of a pitcher plant.

IRA FLATOW: So the pitcher plant then has to wait for it to rain.

TIM REVELL: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Where pitcher plants live, it rains a lot, doesn’t it?

TIM REVELL: Yeah, it rains a lot where pitcher plants are. But it’s also not their only mechanism. They can also use their slippery wax to get their food, too, so it’s sort of an additional way that they can eat their prey.

IRA FLATOW: Is this sort of a spring loaded thing on the lid that it’s waiting for the raindrop to hit and go boing, and then–

TIM REVELL: The way it works is when it sort of hits on the top, that causes some elastic energy to reach the wall to the back of where the lid is. That sort of stores up, but only for a very brief period, which allows the leaf to sort of move– jerk downwards and upwards very quickly. And what that does is it means that the ant then sort of loses its footing and falls down below. And it’s really unusual. We actually don’t know of any other sort of carnivorous plant that uses external energy like this to power a movement to fling an animal towards its digestive pool.

IRA FLATOW: Love to learn something new. Speaking of which, there’s a new study that might make your long Zoom meeting feel a little more bearable. And how do you do that? Using hand signals. Tim, tell me what the research found.

TIM REVELL: Yeah, so if this is to be believed, we’ve all been video calling all wrong. And this is a fun story from Chris Stokel-Walker for New Scientist where he spoke to some researchers at the University College London. And they’ve been testing hand signals, which they taught to students during seminars, which I do feel that could have gone a lot worse than it did. And they recruited 120 psychology students who were taught nine different gestures.

So these included putting your hand over your heart to signify empathy, thumbs up and thumbs down for agreement and disagreement, and putting your hand on your head to ask a question. And then half of the group had seminars with the gestures and half of the group had seminars without the gestures. And then afterwards, they did surveys, and they did a big analysis. And they concluded that the gestures vastly improved the seminars for all involved.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow. Yeah, so it’s like being in class a little bit more.

TIM REVELL: Yeah, I guess it’s like, we’re so used to just staring at a screen and not giving anything away that maybe you just need that extra prod to give the person at the other end of the Zoom call some sense of whether you’re enjoying things, whether you have questions, what you feel about it.

IRA FLATOW: Been there, done that, Tim. Thank you for bringing that to us. Tim Revell, deputy US editor for New Scientist based in New York.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.