Our Ancient Obsession With Capturing The Moon

12:05 minutes

This story is part of our celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. View the rest of our special coverage here.

This story is part of our celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. View the rest of our special coverage here.

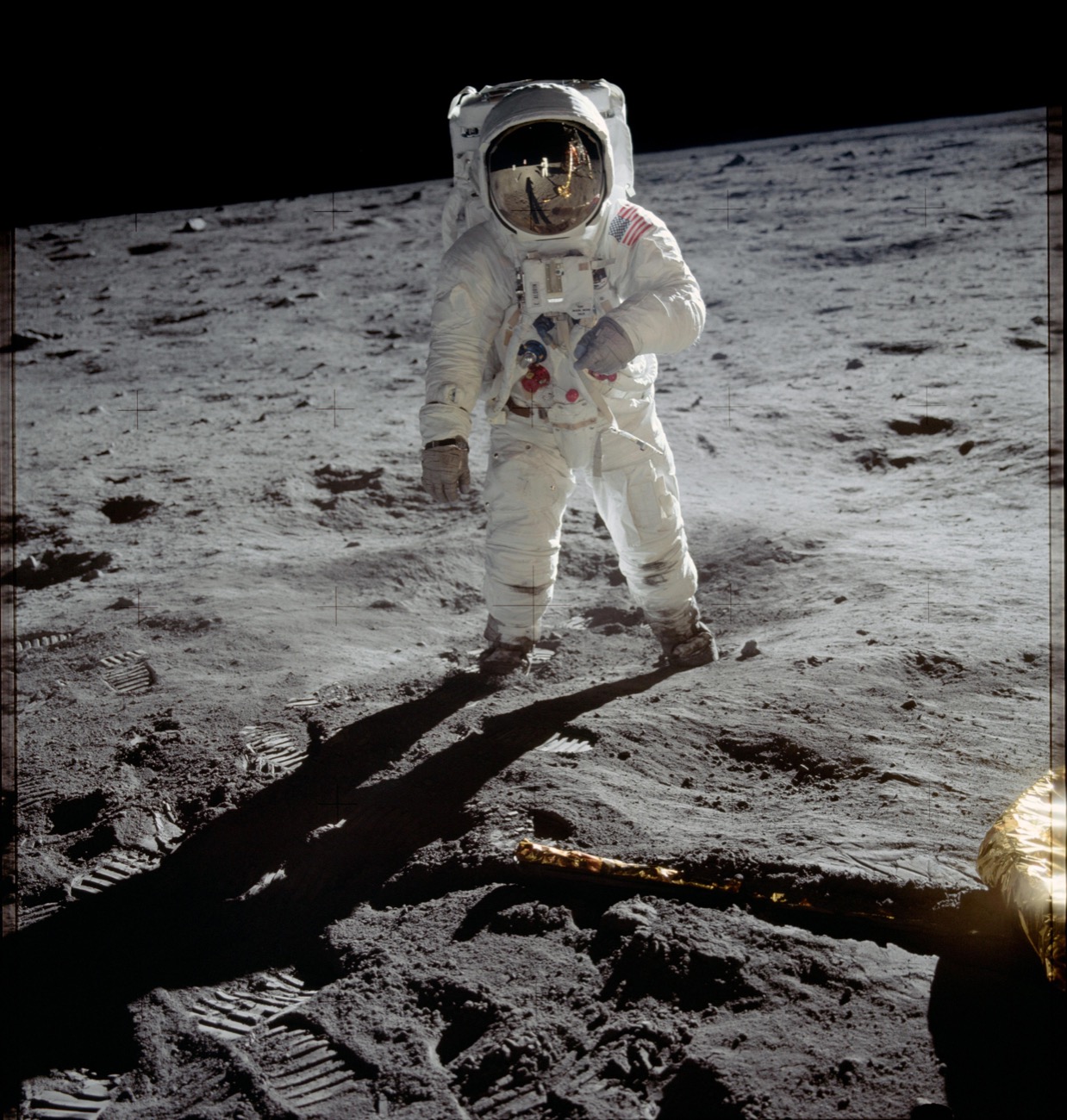

Most of us remember that iconic photograph of the Apollo 11 moon landing: Buzz Aldrin standing on a footprint-covered moon, one arm bent, and Neil Armstrong in his helmet’s reflection taking the picture.

But there’s a much longer, ancient history of trying to visually capture the moon that came before the 1969 photo—from Bronze Age disks with crescent moons to Galileo’s telescope drawings to 19th-century photos and modern photographs. For millennia, we’ve been obsessed with the moon’s glow, its craters and blemishes, its familiar, but mysterious presence in the sky. The moon has mesmerized experts from all fields of study, from scientists, historians, curators, to artists, including this segment’s guest, Michael Benson. Benson is a filmmaker, artist, and author of Cosmigraphics: Picturing Space Through Time, a history of humanity’s quest to visualize the moon and space. In his own art, he uses raw data from space missions to create lunar and planetary landscapes.

Benson isn’t the only person who’s thinking about how science and art has impacted how we see the moon. Mia Fineman recently curated Apollo’s Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The exhibit explores how humanity has interpreted the moon through drawings, paintings, and photographs for the last 400 years.

Until humanity used telescopes, probes, and crewed missions to explore the moon, it was rather nebulous. “People thought of the moon as a perfectly smooth, unblemished orb,” says Fineman. The invention of the telescope and Galileo’s remarkably accurate line drawings “completely changed the human conception of what the moon was like before this. It was a planet, just like our planet. And that meant that it had a terrain that could be mapped and possibly even visited someday. It also meant that there might be inhabitants there.” And contrary to how the church felt about Galileo’s heliocentric theories, they were surprisingly accepting that life could exist elsewhere than Earth.

“In the Protestant church in the 18th century, there was this theory called the ‘plurality of worlds,’” Fineman says. “It was a doctrine that said that if we know that God is omnipotent, why would he only create life on one planet? He’s so powerful that he would create life on every planet. God must have created other worlds besides our own. And so the moon, people speculated, was one of these worlds.”

The speculation of potential lunar life continued to be represented in fascinating ways throughout the next few centuries. While new celestial worlds like the moon were being studied more closely, another new world came into view for Europeans: the Americas. A piece from the 1760s called Pumpkins Used as Dwellings to Secure against Wild Beasts by Filippo Morghen, imagines a lunar landscape populated not by desolated fields of dust and mountains, but by creatures living in giant pumpkins in a swamp.

“A lot of the fantasy about what the moon looked like was very similar to what was being reported by explorers,” says Fineman. “[The pumpkin] was a new world vegetable. That was strange and unfamiliar to Europeans.”

The first photos of the moon were taken earlier than you may think—in 1840. “As soon as photography was invented, people wanted to use the camera to photograph the moon,” Fineman explains. Daguerreotypes, the earliest form of photography, had just been invented a year earlier in 1839 and early photographers were already hard at work to capture the moon as it never had been before.

One hundred and thirty years later, humanity began experiencing the moon firsthand. But one of the most important images that came out of the crewed moon missions wasn’t of the moon itself, but of the Earth. Earthrise, taken by Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders, captured our planet as it never had been before—in full color, partially covered in shadow.

“The fact that [it was] in color really created this strong impact,” Fineman says. “At the time, the astronauts, poets, writers, journalists all talked about how amazing it was that the Earth is the only spot of color in the universe that we can see. Everything [else] is black or gray, and the Earth is this living thing. It really inspired the global environmental movement.”

But despite centuries of research, Fineman can’t help but feel that the moon is still elusive. “It’s a bundle of contradictions. We can see it all the time with the naked eye and yet it’s too far to get to, at least not easily, and there’s one side of it that we never see. So it’s always kind of mysterious.”

The moon’s obscurity lures both art and science. As more research is conducted, scientists uncover more questions about Earth’s constant satellite, continuing to ignite imaginations.

“What I’ve learned in doing this exhibition is that science and science fiction go hand in hand, and there’s a real interplay between them,” she says. “Science influences ideas about science fiction as soon as there’s a scientific discovery. And then science fiction influences science because scientists are often motivated by the imaginings of artists and writers.”

Apollo’s Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City until September 22, 2019.

Michael Benson is an artist and filmmaker. He’s also the author of Cosmigraphics: Picturing Space Through Time (Harry N. Abrams, October, 2014)

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

You probably know that famous photograph that Neil Armstrong snapped of Buzz Aldrin on the moon just after Apollo 11 landed. Buzz is standing, one arm bent. And in the reflection of his helmet, you can see Neil taking the photo.

But for centuries, scientists, artists, and filmmakers have been trying to see the moon, capture all of its craters and blemishes, and imagine what could be up there. Well, now a new exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York called “Apollo’s Muse” explores those centuries of obsessive moon shots and how they’ve shaped scientific discovery and the artistic imagination. Science Friday’s Camille Petersen took a trip with the exhibit’s curator Mia Fineman.

MIA FINEMAN: In order to tell this story, we needed to include a lot of different kinds of objects. This is a book by Galileo Galilei. It is a record of his observations through a telescope in 1609. Galileo’s drawings and descriptions completely changed the human conception of what the moon was like. Before this, people thought of the moon as a perfect, unblemished orb.

This section of the exhibition deals with the moon of the imagination. What we’re hearing is actually a new soundtrack for an old film. It’s George Melies’ Trip to the Moon, which he created in 1902. That’s the image of the man in the moon being hit in the eye by the astronomers’ rocket ship.

These are some artists’ renderings from the 1760s. It shows the moon as a place with people on canoes and giant pumpkins in which the moon people live.

CAMILLE PETERSEN: Why the pumpkins?

MIA FINEMAN: Yeah. I guess they thought, well, where it would moon people live. It was a new world vegetable. So that was something that was strange and unfamiliar to Europeans.

So now we can move into the space race room. Most people know these pictures. Earthrise shows the earth floating above the horizon line of the moon. And The Blue Marble is a picture of just the planet Earth with the blackness of space around it. The fact that these were in color was what really created this strong impact, that the Earth is this living thing.

CAMILLE PETERSEN: Why do you think the moon has been so captivating for centuries?

MIA FINEMAN: It’s a bundle of contradictions. We can see it all the time with the naked eye. And yet it’s too far to get to. It’s always kind of mysterious. It’s constant, and yet it’s always changing. It’s just a paradox that’s hanging out in the sky.

IRA FLATOW: That was Mia Fineman from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York talking to our Camille Petersen.

My next guest is here to talk more about the moon’s visual past, present, and future. Michael Benson is a filmmaker, artist, and author of Cosmographics, Picturing Space Through Time. Welcome back to Science Friday.

MICHAEL BENSON: Well, thanks, Ira. Good to be with you.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, it’s nice to have you. And I want to tell our listeners that they can see all of these images we’re talking about up on our website at sciencefriday.com/moonart.

Let’s go back, Michael, a few millennia to 1600 BC. Give us the depiction of the moon. What did they know about it then?

MICHAEL BENSON: Well, at that time, the moon was key in helping to determine when to plant and when to reap what you sowed. And in fact, the moon’s phases are kind of the monthly metronome or temporal backbone of any calendar divided into 12.

And we don’t think about this. But the word month is a cognate of the word moon.

So at that time, the moon really helped to understand when to plant, when to harvest. But in general, it was stirred fascination and a need to understand. I think more than any other object in the sky, with the possible exception of the sun, the moon influence the imagination of early humans and caused this puzzlement and sometimes terror when you had an eclipse.

So I have a thesis that all of our contemporary technologies, every cell phone, every laptop, et cetera derived from this history of technology which originated in European astronomical clocks and then the need to miniaturize those and the watchmaking finesse and precision which resulted from miniaturizing astronomical clocks.

And the lead indicator, of course, of the month is the moon. And then also the eclipses were hard to track. And that also was a puzzle.

IRA FLATOW: Was the Nebra sky disk back in 1600 BC, is that the oldest known graphic?

MICHAEL BENSON: Yes, the Nebra sky disk was unearthed in central Germany in 1999 by, effectively, grave robbers. And then the German police recovered it a few years later. And there was a lot of skepticism.

It’s about the size of a vinyl record. It’s 12 inches wide. It’s got gold, two representations of the moon in gold. One is a full moon, and one is a crescent moon. And you see the Pleiades on it.

And after a lot of testing, it was determined that the thing was actually real. It wasn’t some fake or something, because nothing like that had been seen before.

We’re talking about roughly the period of Stonehenge. And it has since been effectively endorsed as the world’s first portable astronomical calculation device.

IRA FLATOW: And then the moon made an appearance in the 14th century book Dante’s Inferno, right?

MICHAEL BENSON: Oh, yeah. In Dante’s Inferno, you have Dante and Beatrice rising towards the moon. It’s actually early spaceflight. There’s some beautiful Renaissance depictions of that, illuminated manuscripts of them rising into the cosmos.

IRA FLATOW: And then you have, in the 19th century, people started making plaster models of craters, of all things.

MICHAEL BENSON: Yeah. That was in part because early film was simply not fast enough to capture the moon. And so beginning with John Herschel– I have an image in my book Cosmographics which is an early photograph of a crater made in plaster.

And I think that Mia Fineman has some later depictions. And I also have some of those in my book of plaster models of craters, because then they could be photographed in a controlled studio environment with these slow emulsions of the 19th century.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of slow emulsions, wasn’t one of the first films ever made a film about a man in the moon getting hit in the eye by a big bullet shot from a giant cannon? I remember seeing that.

MICHAEL BENSON: Right. I just wrote a piece which should be in The New York Times this weekend. And it’s about later films. And it’s actually about how some of the early geniuses who came up with multi-stage rocketry were provoked by Jules Verne who depicted a cannon shell taking space travelers to the moon. And they realized that a cannon would immediately convert any astronauts inside to, basically, tomato juice on launch.

And so in George Melies’ film, you do have a Jules Verne-style cannon shell lodging itself in the eye of the moon.

IRA FLATOW: But there have been so many films and movies where the moon has an emotional pull or is a stepping stone to further space exploration, like 2001: A Space Odyssey, right?

MICHAEL BENSON: Right.

IRA FLATOW: Well, what is it about the moon? Why are we so obsessed with it?

MICHAEL BENSON: Well, I think that there’s something symbiotic in the relationship between representation and understanding. And understanding doesn’t necessarily precede the representation. Sometimes the representation can help with the understanding.

Werner Heisenberg warned his fellow scientists– Werner, that’s the German physicist. He said, contemporary thought is endangered by the picture of nature drawn by science. The danger lies in the fact that the picture can now be regarded as an account of nature itself rather than our picture of it.

But by the same token, how else to develop? You make a model. You study it, perhaps react against it.

So Copernicus was reacting against all of those depictions of an Earth-centered cosmos. He needed all of those erroneous graphic depictions of an Earth-centered cosmos to understand the true design of the solar system.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think that the Apollo 11 landing changed anything about our captivation with the moon’s image and how we look at it?

MICHAEL BENSON: That’s a really good question. I think that it showed that we can achieve extraordinary things if we put our mind to it.

You mentioned 2001: A Space Odyssey. That moon– that moon. That film came out a year before the Apollo landings, the first Apollo landing, which is, obviously, the anniversary this weekend. And I think that that plus the actual landings showed us the next stage.

So for example, 2001 marked the change from the Western– the Hollywood paradigm was the Western until Kubrick and Arthur Clark made this extraordinary film, which was the highest grossing film of ’68. And suddenly, the big budget science fiction spectacular was a going proposition. And since then, we’ve had innumerable versions of that, innumerable different types of sci-fi space spectacular. That shows that we kind of reached a next phase.

IRA FLATOW: Do we have a next phase now that you see about how we’re going to depict and visualize the moon?

MICHAEL BENSON: Well, I don’t know about visualizing it. But certainly, we seem to be at a next phase of spaceflight with all of the privately funded, Elon Musk and SpaceX and so forth. And then the Chinese seem quite serious about sending people there. So I think we are at our next phase.

The depiction of it, we’ve had a spacecraft orbiting the moon called Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter for a few years now. And we have extraordinarily accurate depictions of the moon from that. So our understanding of the moon’s surface is quite accurate.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think that we have lost our romance with the moon then, because we’re so scientifically and technically involved with looking at it?

MICHAEL BENSON: I don’t know. I was just driving back to Ottawa, where I live these days, the other night. And the full moon rose over the hills north of Ottawa. And it was so extraordinarily beautiful. I don’t think there’s really a danger of that.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I–

[CHUCKLING]

I have to agree with you. It is something that does not lose its flavor and especially now when we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11.

I want to thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today. And good luck on your next moon depiction.

MICHAEL BENSON: Oh, thanks, Ira. It’s good to be on WNYC again.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, it’s nice to have you. Michael Benson, he’s a filmmaker, artist, and author of Cosmographics, Picturing Space Through Time.

We’re going to take a break. And when we come back, a conversation we taped this spring at the US Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. You know that Huntsville is a very famous place for space exploration and also for preserving space memorabilia and history there. We’re going to talk about preserving space history through archives and museum collections.

Stay with us. We’ll be right back for that conversation after the break.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Camille Petersen is a freelance reporter and Science Friday’s 2019 summer radio intern. She’s a recent graduate of Columbia Journalism School. Her favorite science topics include brains, artificial brains, and bacteria.

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.