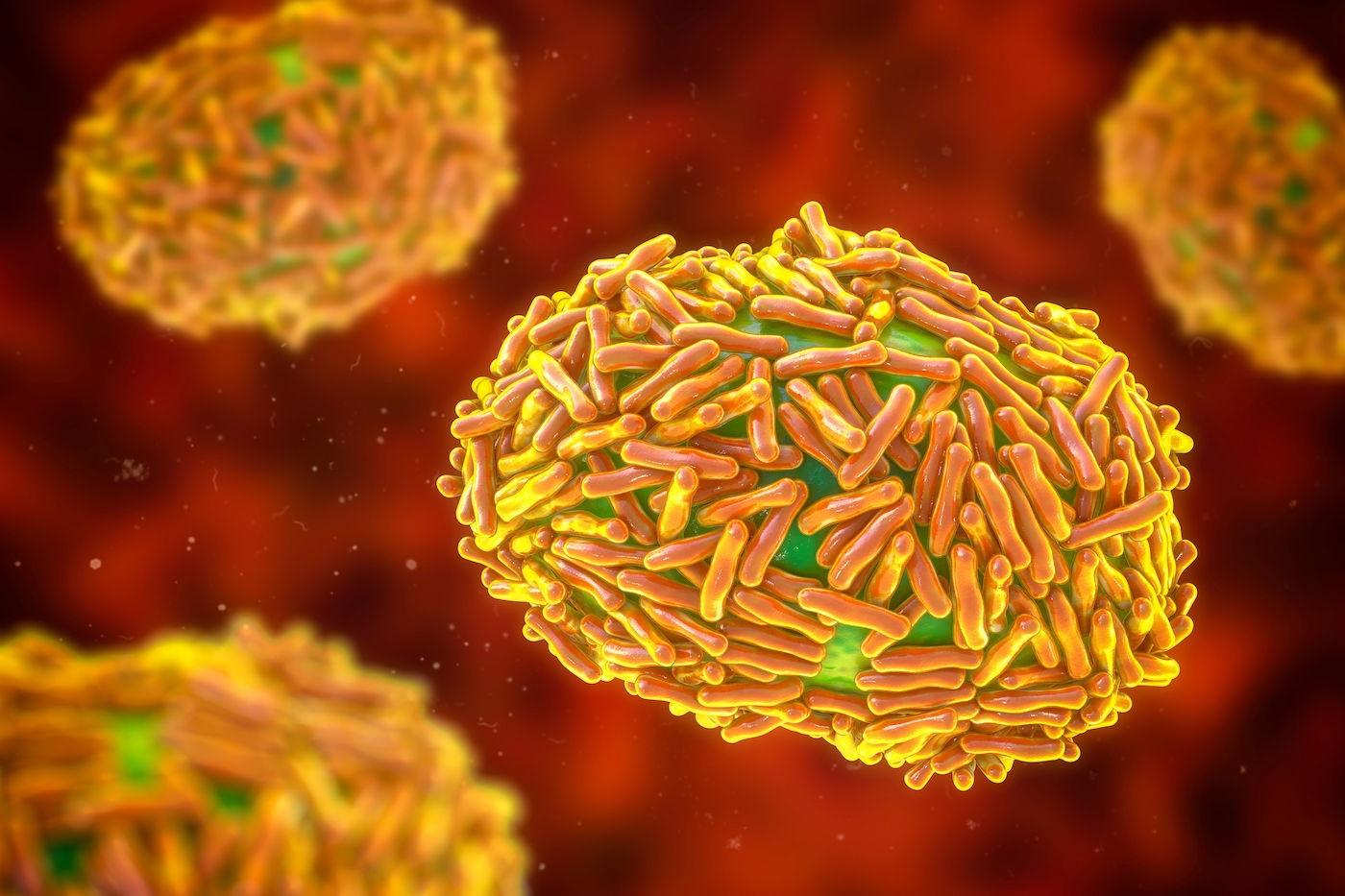

What You Need To Know About Monkeypox

17:22 minutes

Last week, the White House declared the monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency.

Currently, there are a little over 9,000 confirmed cases in the United States, and just under 30,000 worldwide. Since the end of May, monkeypox has been spreading in countries where it has not been previously reported.

The virus is mainly spreading within gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men. And because of that there is stigma associated with the outbreak.

Ira talks with Rachel Roper, virologist at the Brody Medical School at East Carolina University, and Perry Halkitis, dean of the Rutgers University School of Public Health, to explain the basics of transmission, answer listener questions, and debunk misinformation about the monkeypox outbreak.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Rachel Roper is a virologist and professor of microbiology and immunology at Brody Medical School at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina.

Perry Halkitis is the dean of the School of Public Health and director of the Center for Health, Identity, Behavior & Prevention Studies at Rutgers University in Piscataway, New Jersey.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. You’ve probably heard the headlines about monkeypox. As of last week, the White House declares the outbreak a public health emergency.

Currently, there are a little over 9,000 confirmed cases in the US and just under 30,000 worldwide spreading in countries where we’ve never seen it before all since the end of May. The virus is mainly spreading within gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men. And because of that, there’s a stigma associated with the outbreak.

A lot of you have written in with your questions about monkeypox. And joining me now to answer those questions are my guests, Rachel Roper, PhD, virologist and professor of microbiology and immunology at the Brody Medical School at East Carolina University based in Greenville, North Carolina, and Perry Halkitis, PhD, Dean of the Rutgers University School of Public Health based in Piscataway, New Jersey. Welcome both of you to Science Friday.

RACHEL ROPER: Thank you, Ira.

PERRY HALKITIS: Hi, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Dr. Roper, let me begin with you. Let’s start with the basic questions here. We’ve gotten so many questions from our listeners to clarify stuff they’re seeing, misinformation circulating. How does monkeypox spread?

RACHEL ROPER: So monkeypox can spread through the respiratory route if you’re very close to someone, but the way that this variant is spreading is through close personal contact, skin to skin contact. And like you said, mostly it’s spreading now with sexual contact between men who have sex with men. So it’s much less contagious than COVID. You’re not going to catch it through the air like you would catch COVID.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re not going to catch it from touching a surface or clothing that someone else has touched?

RACHEL ROPER: Well, that’s a place where monkeypox is actually more of a problem than COVID would be. Monkeypox– the pox viruses have very stable virus particles. So it can spread more easily on surfaces just because it’s more stable.

So if you go to the CDC website, you can look for how to disinfect clothing and surfaces. It could potentially spread that way. It’s not likely. It’s much less contagious than COVID, but if you’re out somewhere, and you touch a doorknob that someone just touched, and they’ve got monkeypox, you could get it on your hand, and then if you touched your eyes or your face, it could get into your body.

It’s a good idea always, if you’ve been out in the public somewhere, you know, like don’t touch your face while you’re out in the public and especially if you’re touching things. And then when you get home, wash your hands with soap and water. It’s just always a good idea to do that.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Halkitis, as Dr. Roper mentioned, monkeypox can spread during sex, but it’s not a sexually transmitted infection, is it? How has this framing of monkeypox as an STI impacted the public’s understanding of the virus and how policymakers Dole out resources needed to contain the outbreak?

PERRY HALKITIS: Yeah, Ira. That’s a really terrific question. Just to clarify that, when we say sex, right, we don’t necessarily mean intercourse. People can be engaged in intimate relations with each other, they can be rolling around with each other, there doesn’t have to be an act of intercourse for monkeypox to spread.

And so it is not an STI per se, as we might think of syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia. You can be in bed with an individual. You can be kissing that individual. You can be hugging that individual. If that person has an infection, you may become infected.

Now, what’s really interesting here is I think so much of our response over the course of the last few months I think is in some ways been shaped by people’s concerns about how we dealt with HIV in the 1980s and the messaging there, where this disease was attributed to gay men, where gay men were stigmatized. So I think the CDC and other federal officials and certainly local health departments are walking a very fine line here.

The bottom line here is we’ve said this from the beginning of monkeypox, anybody can get it. As my colleague just said, however it is primarily in gay and bisexual men right now who have intimate relations with each other. So our policies in some ways have been shaped by the past and fear of making a mistake right now in the present.

I will say one more thing, Ira. I think our uptake and our response has been a little slow. And one can’t help but think that the response may have been somewhat more quick had a different segment of the population been infected. That’s just the hypothesis. That’s just the conjecture.

Let’s also as we think about this disease and we think about policy not ignore the fact that gay and bisexual men are being infected. I think we have to acknowledge that fact. And I think as a population, we have an obligation to say let’s protect our gay and bisexual brothers. Let’s control the virus in that segment of the population. And then hopefully all of us as a community will benefit.

IRA FLATOW: You know, this sounds so much like the messaging from the 1980s as I recall when AIDS was spreading wildly.

PERRY HALKITIS: It is, Ira, very similar. We’re 41 years into the AIDS epidemic. So let’s just all remind ourselves. We still have COVID. We still have HIV. We still saw like 40,000 new infections of HIV each year in this country. And now we have monkeypox.

When you make a disease, and you call it an STI, when you overemphasize sex, and you make it about gay sex, which is– sex is stigmatized to begin with. Gay sex is even more stigmatized. Then it becomes in the hands of wrong people, like politicians who are seeking to do harm, potentially a very lethal weapon that will stigmatize and sort of diminish the being of the population affected and ultimately deny, in this case, gay and bisexual men the resources that they need in order to combat this virus.

IRA FLATOW: One other question we get is should we be concerned about monkeypox mutating and adapting like COVID-19 has, Dr. Roper?

RACHEL ROPER: Yes. So a good thing that pox viruses are large double-stranded DNA genomes. So those mutate much more slowly than an RNA virus like COVID, SARS-CoV-2. So the mutation rate should be much lower.

But a paper did come out recently showing there were 50 single mutations that have occurred already in the last few years. And that’s probably as monkeypox is adapting more to spread human to human, so it can mutate. It almost certainly will mutate, but it should have a mutation rate much, much slower than COVID-19.

IRA FLATOW: Is there a simple test for monkeypox like we have for COVID? Should we be testing more than we are now?

RACHEL ROPER: My lab can easily test for the monkeypox virus genome or for the proteins. It’s really easy to do. The thing that makes it more difficult is that diagnostic labs have to be certified as properly testing. So they have to test that they get a certain very low number of false positives and a very low number of false negatives with a large sample of human population.

So that’s a much higher standard than just being able to detect it in a research laboratory. So that’s why it’s different, but the CDC has been working with these CLIA certified labs to get them up and running and testing so that we can test more samples at a higher rate. And I think that is important because you can’t find something if you’re not watching for it. And there could be rashes showing up in dermatologists’ offices or in gynecologists or general health practitioners’ offices that we really probably should test.

PERRY HALKITIS: Can I ask Dr. Roper a question? Dr. Roper, I’m curious because I’ve been grappling with this issue, too. Obviously the lesions can occur all over the body. It seems like in this particular outbreak we’re experiencing right now in the gay and bisexual male population, there seems to be lesions that are manifesting primarily in the genital area. Is that different than the way we’ve seen it in outbreaks in the past and could that be an evidence of changes in the virus and the way it’s transmitted?

RACHEL ROPER: So I’m not sure if the location of the lesions relates to the mutating in humans. You do more frequently get lesions on the skin, the face, and the genitals just because it’s more thin skin, and it’s easier to create lesions there. But certainly, the sexual contact, that’s probably some localized lesion to lesion spread. But then people are getting– you can get it on your hands, your feet.

And the hands are especially a problem because people walk around touching things with their hands, and they could be leaving virus on surfaces. And they get lesions in the mouth, too.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah walk us through then, what the typical person should be looking for in their own body.

RACHEL ROPER: So the thing that I worry about is that the first symptoms can be just like many illnesses. You can get fever, chills, be tired, have muscle aches, backache, respiratory symptoms, so sore throat and nasal congestion. Those can be the first symptoms. And the person might not get a rash until four days later. So they might have monkeypox for four days and not know it. So people could get it and end up transmitting it before they realize that they have it.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting. The FDA announced this week that they will be splitting single doses of the vaccine, the most widely used monkeypox vaccine into five smaller doses to stretch the supply. Dr. Roper, is that a good approach to get more people vaccinated? And they’re changing the way the vaccine is injected, too, right?

RACHEL ROPER: Yes. I think that’s a reasonable approach. If you want to stimulate a good immune response, you usually want to use a lot of antigen, a lot of the vaccine. But you can get a reasonable well response with a smaller amount of the antigen that’s in the vaccine. So given our limited supply right now, I think it’s probably a good idea to go ahead and reduce the dose like they are planning to do.

And that’s the JYNNEOS vaccine. The other vaccine we have is called ACAM2000, and it’s very strong and very effective, but it has some safety concerns. And so that’s why they’re recommending using the JYNNEOS vaccine now for monkeypox.

IRA FLATOW: And the vaccine now is talking about being injected just underneath your skin, right?

RACHEL ROPER: Yes. Yeah, the subcutaneous. The ACAM2000 in the original, the old vaccine, they put a drop of virus on your skin, and they puncture 15 holes in your arm.

IRA FLATOW: I remember that. Well, I was a little baby. I don’t remember– but I remember seeing doctors do that.

RACHEL ROPER: Yeah, and then you would get a lesion, a blister, and eventually it would scab over. And most of us who have had this vaccine have a scar in our upper arm. It’s the round dime sized scar on the upper arm of people that are 50 years or older generally.

And so now with the JYNNEOS vaccine, they don’t do that multiple hole poking mechanism they used to do. But they’re injecting subcutaneously.

IRA FLATOW: We got a question from listener Rachael, who wants to know if you think the smallpox vaccine should be made available to healthy adults as we ramp up production of the monkeypox vaccine.

RACHEL ROPER: So the smallpox vaccine is the monkeypox vaccine. Smallpox, monkeypox, and vaccinia virus, which is what the vaccine strain is are all in the same genus. They’re closely related viruses. So the government and the scientific community has focused on smallpox for the last 30 years because that’s really what we’ve been concerned about. So all of these vaccines and drugs were designed for smallpox, but they also work for monkeypox, and that’s our current problem. So that’s why those vaccines and drugs are being used for monkeypox now.

IRA FLATOW: So if I got those scratches when I was a kid, are they still good? Do I still have immunity?

RACHEL ROPER: Yes, you probably do have some residual immunity, but immunity does wane over time. So the older you get, the less strong your immune response is and also the longer ago that you had the vaccine, the less likely you are to have strong protection from it. But this monkeypox that’s circulating right now is a less virulent strain.

It’s the West African strain, so that’s really good news. It only has a fatality rate untreated around 1%. And in the US, we have drugs for it. We have good medical treatment. So it’s unlikely to kill people in the US.

It’s going to be much more of a problem for someone who’s immunocompromised or also potentially people that have eczema or other skin inflammatory conditions. It would be more dangerous for them and for pregnant women. It can cross the placenta. So it is dangerous for certain subgroups of people.

PERRY HALKITIS: I think your line of questioning raises some interesting ideas, which is there are people like myself, who’s 59 years old right, who clearly had the smallpox vaccine in an era– and I’m a gay man, right? But I’m not a gay man who’s 25 years old and socializing at clubs every single night of my life, thank God. And you know, it makes me wonder as we’re thinking through the vaccination strategy, and I appreciate my colleagues’ comments that we want to get as much vaccine in people’s arms as possible.

I don’t love that it’s being used in a way that it wasn’t really tested for, but I can live with it. But I wonder if there should be some more nuanced thinking about which members of the gay, bisexual population might be most in need of the vaccine. Should we start with the 20 and 30 somethings and the HIV positive population? I think– I’m not saying that I have the answers to these things, but I think there is a more complex thinking that should go on that might benefit the whole population generally in a more effective way.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I remember Larry Kramer saying in the 1980s that gay people were getting infected because they were having too much promiscuous sex. Is that the kind of complexity you’re talking about?

PERRY HALKITIS: Actually, Larry, who was a dear friend, actually said we should stop stop– stop having so much rampant anonymous sexual partnering. And the fact of the matter is it only takes one person to infect you with HIV. So the choice of a wrong partner who you’re monogamous with could still infect you with HIV.

No, I think in this particular situation– again, I’m walking a fine line here. It is probably not a bad idea for individuals who are not yet vaccinated to consider their behaviors and to use harm reduction strategies to engage in sex, perhaps not close intimate contact, perhaps postponing until somebody is vaccinated. There are things you can do to protect yourself. We’re not saying that you should completely stop having sex, but perhaps having sex that might not put you at risk in the absence of a vaccination.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. I also want to bring up the disparities in who even has access to this limited supply of vaccine. Poor and Black men have lower vaccination rates, right?

PERRY HALKITIS: I remember at the beginning of COVID doing a set of interviews about the disease and how it was spreading, and reporters were asking me why is it the Black population, the Latin population? I’m like why are we surprised at this when we look at health disparities in our country? They tend to manifest in those populations that have less access that are more marginalized.

And when you think about the Black community, Black population as compared to the white population, certainly more levels of discrimination, less economic well-being, and as a result, increased health disparities. So it’s, of course, manifesting the same way in the gay and bisexual population. The LGBT population is not monolithic.

And the latest data show that Black men are more likely to not be vaccinated and more likely to be infected with monkeypox in a very similar way that in the United States the majority of infections that we’re seeing for HIV at the present time is young Black gay men. And so it’s like history repeating itself here, and I think what this speaks to is making sure that we provide access to the vaccines in a way that’s easy for people who might not have the means to take off of their work or travel long distances, to bring it to neighborhoods that primarily serve racial and ethnic minority populations and being really strategic in getting the vaccines in those arms of those folks who might not normally have access.

This is a virus that we know and that’s been around and has been infecting humans since 1970. So we’re way ahead of the game. I wish our response had been better given that the fact that we’ve known about this virus for such a long time.

IRA FLATOW: Good place to end. Great discussion. Thank you both for illuminating and taking time to talk with us today.

RACHEL ROPER: Thank you.

PERRY HALKITIS: What a pleasure. Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Rachel Roper, virologist and professor of microbiology and immunology, Brody Medical School at East Carolina University. That’s in Greenville, North Carolina. And Dr. Perry Halkitis, PhD, dean of the Rutgers University School of Public Health.

We’re going to take a break, and when we come back, what if the galaxy we live in could talk or even write a sassy tele memoir? Well, I have news for you. Stay tuned. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.