Were Neanderthals Artists?

16:51 minutes

Since the first fossil finds in the 19th century, many have considered Neanderthals, a “sister species” of Homo sapiens, as a primitive species. Their reputation stands as unsophisticated and brutish—and not artistic. But in 2012, anthropologists determined the age of hand stencil paintings discovered on the walls of caves in Northern Spain to date back at least 40,800 years, falling right in the time period where both Neanderthals and early modern coexisted in Europe. Researchers could only speculate: Were the symbolic masterpieces created by early modern humans or were they done by the hands of Neanderthals? Could these stencils be evidence of Neanderthals’ cognitive abilities?

Now, a new finding suggest an answer. A research team from University of Southampton and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology studied red and black pigmented cave art—from animals, geometric patterns, and hand stencils—in three of the caves in Cueva de los Aviones, a grotto in Southern Spain. Thanks to refining the use of uranium-thorium dating (a dating technique that is more accurate at determining age estimates than radiocarbon dating), the researchers found that some of the motifs are more than 64,000 years old—painted at least 20,000 years before modern humans arrived in Europe. That means the paintings could be none other than Neanderthal, the researchers conclude in their study in Science.

[A fossil find pushes back Neanderthal-human mixing.]

Study co-author Chris Standish, an archaeologist at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom, and Harvard archaeologist Christian Tryon, who was not affiliated with the new research, join Ira to discuss the recent findings and what the cave art might suggest about the similarities between Neanderthal and human cognitive abilities. Plus, venture inside the caves in Southern Spain with the research crew and see the ancient masterpieces of the Neanderthals.

Chris Standish is a Research Fellow in Archaeology at the University of Southampton in Southampton, United Kingdom.

Christian Tryon is an associate professor of Archaeology at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Our ideas about Neanderthals have come a long way in the last few decades. First thought to be thick-browed strangers, we have learned that they were genetically much like us and even interbred with humans during a period when both Neanderthals and modern humans lived together in Europe. And there are still Neanderthal traces in the genes of anyone whose ancestry lies outside sub-Saharan Africa.

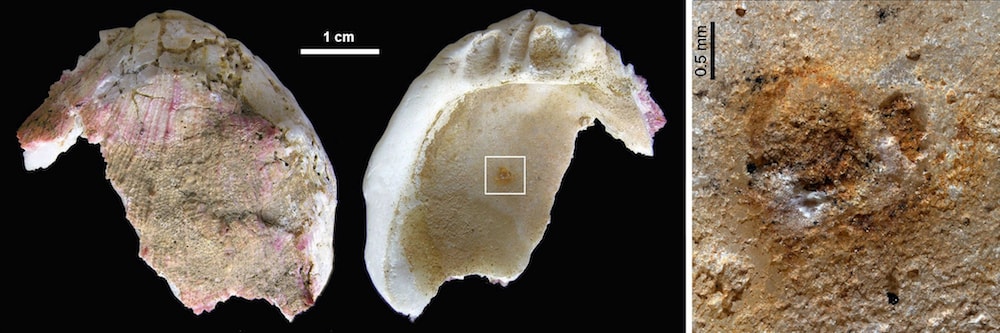

But what were they like and why didn’t they survive while we did? Some theories still point to brains. In fact, the word Neanderthal is still used as a slur to insult someone’s intelligence or sophistication. And while archaeologists can point to pigmented shell jewelry as a sign of rising abstract thought in our ancestors, there’s less evidence that Neanderthals thought symbolically or made art.

That’s changing now because new research makes exactly that claim for Neanderthals. A team of scientists are using uranium dating of tiny calcite crusts over cave paintings in Spain to say that these paintings had to be older than 60,000 years. A time when, so far, there is no evidence of modern humans living in Spain.

So, the conclusion? Well, the Neanderthals were responsible for hand prints and red lines painted in ocher. And the conclusion from that? They thought abstractly and symbolically just like us. And that work is published in the journal Science.

Here to explain some of the new research is Dr. Christopher Standish, a co-author on that paper and an archaeologist at the University of Southampton in the UK. And we have pictures of the cave paintings in question up on our website at sciencefriday.com/caveart. Welcome to Science Friday.

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Hi, thank you.

IRA FLATOW: So how sophisticated is the art in these caves? Are we talking about the horses we’ve seen in other caves around or is something much simpler?

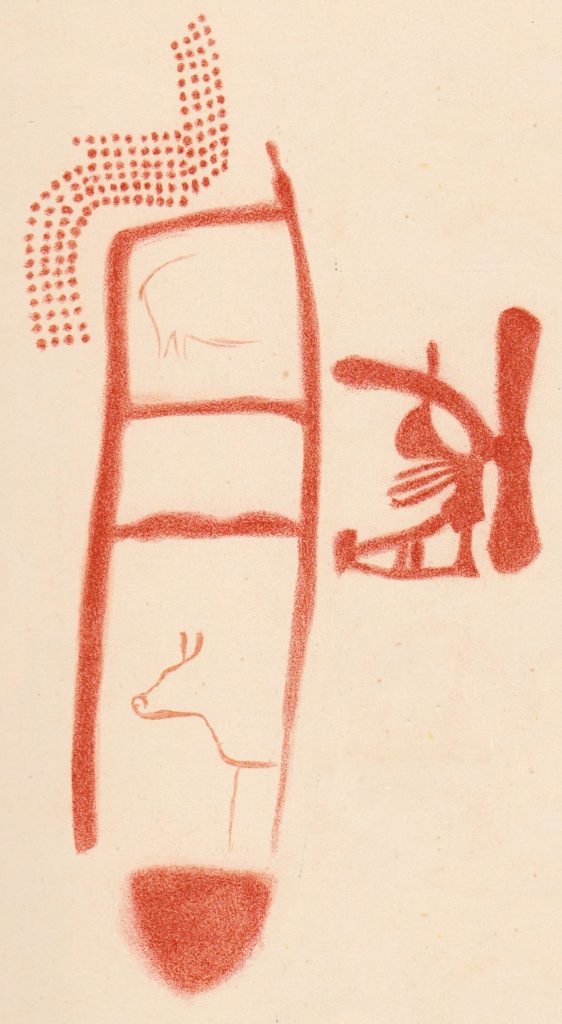

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: It’s slightly different to the more famous images that you see from sites like Chauvet, and Lascaux, and Altamira of the polychrome animals; bison, and horses, and things. Some non-figurative art is made from red pigment. Things like linear forms, one of them is called a scalariform. So it’s a ladder-like shape, part of a more complex panel. Hands stencils and general patches of pigment on stalagmitic formations.

IRA FLATOW: Give us an idea of how you dated the paintings. You were looking at crusts that had formed on top of them.

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Yeah, absolutely. So these crusts are made from calcium carbonate and they’re essentially tiny speleothem. So secondary carbonate formations along the lines of stalagmites and stalactites. So they form in the same way.

Rain water passes through the soil profile above a cave. This gets enriched in carbon dioxide. So it becomes a weak acid. And when it percolates through the limestone below, it dissolves up small amounts of calcium. When this water enters the cave below, the carbon dioxide is released. And this leads to precipitation of calcite and you get the formations of these speleothem.

Now, its possible to use uranium-thorium to date speleothems. This has been done for decades now. It’s a technique that’s used significantly by climate scientists when they’re looking at elemental differences in stalagmites. And that’s because the uranium and thorium have different solubilities.

So uranium is very soluble, which means it gets dissolved up by these waters. Whereas thorium is insoluble, so it isn’t. The 238-uranium, which is the isotope at the beginning of decay chain we are interested in, has a half-life of about 4 and 1/2 billion years. And when the calcite forms, a clock is essentially beginning. And by measuring the amounts of 238-uranium, 230-thorium, and one of the intermediate isotopes, we can calculate the age of the speleothem formation.

And just like stalagmites and stalactites grow, you get theses small little crusts forming on top of pigment. So if we date those, we know that the art underneath must be older. We’re getting a minimum age for the art.

IRA FLATOW: What is the minimum age your getting?

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: So in each three of these sites we’ve got minimum ages of 64,000 years or older.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And there’s no maximum age yet?

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Well, one of them, we have to get a couple of maximum ages. This is a lot more difficult. It’s quite a rare occurrence because it relies on the art being applied onto a speleothem, so sort of being used as a canvas. And the only way we can sample this is generally when they’ve fractured naturally. And so we can get in from the side because we never sample through the pigment.

IRA FLATOW: So what maximum age did you come up with?

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Well this is for a different motif to the ones that we have the minimum ages of 64,000 years. So there is one motif that we can date to between 45,000 and 48,000 years ago. So that’s the minimum and a maximum. Unfortunately, there’s no maximum for the motifs we dated to even earlier.

IRA FLATOW: So tell us why 60,000 years is such an important number for the Neanderthals.

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Yeah, well current evidence for the arrival of Homo sapiens in Spain places them around 42,000 years ago in the north. Now, there are various estimates one or two thousand years either side of that. But it’s essentially around 42,000 years.

In the south of Spain, this is probably a little bit later. Recent work down in the southeast suggests about 37,000 years. So there’s no evidence of Homo sapiens before 42,000 years ago anywhere in Iberia. So the fact that this art is being produced prior to 64,000 years ago means that it’s a different Hominin group that must have been creating it. And in this case, it’s the most likely scenario that it’s Neanderthals.

IRA FLATOW: Is age all we need to decide that the Neanderthals made these paintings?

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Sorry, can you repeat that?

IRA FLATOW: Is the age all we need to secure the idea that Neanderthals made these paintings?

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Well, it’s about the best we can do. There’s no other way to link the art to a particular type of human. They’re notoriously difficult to date as they are already. So, we just have to work out the age of the art and then compare it to the archaeological record to see which groups were living there.

IRA FLATOW: And how is this finding being accepted? Do people say, we need more, we got to do another one? This is so fantastic, we need some more evidence?

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Well, I suppose it’s hard to see. We’ll have to wait to see till the dust settles. But, I mean, a lot of people are acting very positively about it. We have been holding onto these old dates for a little while now.

The first one was probably collected a couple of years ago. But we waited until we found some supporting evidence to go with it. So it’s not like we’ve just got one date stating this. We’ve got three samples from three different caves and they’re all made up from individual sub-samples themselves. So we’ve waited for a decent body of evidence to help support our interpretations.

IRA FLATOW: That’s good. That’s very wise. I want to bring on another archaeologist not involved in this work. Dr. Christian Tryon, associate professor of anthropology at Harvard. Welcome, Dr. Tryon.

CHRISTIAN TRYON: Hello, and thank you for having me on.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, you’re welcome. Tell us how well this Neanderthals-made cave art fits with everything else we’ve been learning about how they lived and how smart they might have been.

CHRISTIAN TRYON: Yeah, it’s a nice part of the picture. We’re constantly learning more about Neanderthals, what we think they were doing, what we think they were capable of. And this adds an extra wrinkle in that if Neanderthals are making these things that we call art, that implies a level of cognitive ability, sophistication, of viewing the world, that I think is very familiar to us as Homo sapiens, as modern humans. It tends to make them more like us.

IRA FLATOW: Chris, they had other cultural ways that we know about, not just as painters.

CHRISTIAN TRYON: That’s right. Like living people, different groups of Neanderthals did different kinds of things. So some of them seem to have buried their dead, for example. Some of them seem to have cared for the old, or the infirm people, who needed to be supplied by the rest of the group. Things that, again, we link as very human-like behaviors.

And so this is part of a bigger picture. It’s nice. It lets us move away from older studies that really focus on what they ate or what sorts of tools they made. And more socially interesting kinds of things about who they were.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about the art a bit. Why is art so connected to this idea of symbolic thinking? And why is symbolic thinking an important trait?

CHRISTIAN TRYON: That’s a really good question. We’re humans, we always think that we’re special. So we think this is something that we do and other groups– For example, people look for other living primates like chimps, gorillas, these things. Symbolic or abstract thinking is often believed to be something unique to us.

And so when you think about some of our closest ancestors, which Neanderthals are, but they’re extinct, it becomes a big question. How like us were they? So the ability to think abstractly with symbols is a big part of that question. I think the root is really, how much like us were they?

And the reason this is important is we’re here and they’re not. Right? And it’s one thing to think about, OK they went extinct, we’re still here, maybe we were better adapted and that’s the end of the story. But it’s quite a different story if you start to think, well, they had art, they bury their dead, they thought abstractly. And then our role in their extinction becomes, I think, a more profound question.

IRA FLATOW: Chris, would you agree?

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Yeah, absolutely. And this evidence of cave art is just adding further to the other evidence for symbolic and ornamental [INAUDIBLE]. There’s other evidence that they are using perforated shells, shells stained with pigment, bird feathers, and even eagle talons. So this is all presumably as personal adornment.

This is comparable to what we see from modern humans at a similar time. So yeah, absolutely. It looks like there’s a building level of evidence to suggest they do have a slightly higher level of symbolic thinking than we previously thought.

IRA FLATOW: No one is saying that this pigment on the cave wall is an accidental splash or anything? It is genuinely put on there as a piece of artwork?

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Yeah, we’ve got this range of motifs. The most convincing from this perspective is the hand stencil. This is from a cave called Maltravieso in central Spain.

Now, this is quite a narrow cave that’s got about 60 hand stencils in it. And it would require them to prepare a light source, enter the cave with some pigment prepared, and then they’ve actually got to hold their hand up and then spray this pigment over the hand. Probably out of their mouths in order to create this stencil. So that’s certainly not something that’s accidental.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International.

I can imagine the people who stumbled upon a stencil of a hand on a wall must have been aghast at seeing that in a cave and certainly thinking it was 60,000 years old.

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Yeah, these are quite common motifs the world over, in fact. They’re found in places like South America, Australia, Indonesia, Egypt. So there’s something quite fundamental about them in that different human groups we’re creating them.

And, interestingly, they often seem to be part some of the earliest phases on different multi-phase sites. So if you’ve got multiple different layers, they’re often at the base. So it’s almost as if there is some kind of a marking of territory situation going on. What they really mean, of course, we really just don’t know.

IRA FLATOW: It’s interesting. And Christian, how does the art from the Spanish caves compare to what we’re finding from humans in Africa during the same period.

CHRISTIAN TRYON: That’s a really good question. Because that is one of the better comparisons you can make. As far as we can tell, for large expanses of the last ice age, you had Neanderthals in Europe, Western Europe in particular, and you had modern humans, Homo sapiens in Africa. So you can compare different continents at the same time.

In Africa, part of it’s geology. The geology is a little less forgiving and the caves that would preserve ancient paintings aren’t as common or may not exist at all. So there’s not as good evidence for cave painting in Africa. And the funding is a little bit less. So, the evidence may be out there, but we don’t have really good, very well-dated ancient African cave paintings.

There are things, I think pierced shells were mentioned. So you do see on sites on either end of the African continent. In the Mediterranean and on South Africa, you see people using seashells and piercing the seashells. Putting a hole in them or sometimes collecting ones they found on the beach that have a hole on them. But clearly wearing them in some way, either as jewelry or sewing them onto things.

In the middle of the continent where you don’t have seashells, you have people using ostrich eggshell beads. By about 40,000 years ago, and even a little bit older, people are breaking up a big ostrich eggshell into little fragments and carefully grinding these beads down, piercing them into holes, and putting them onto strands.

So you have a different tradition, but still modifying things for personal ornamentation by 45,000 years ago. So part of it is a different record, just to what preserve. We’re lucky to have anything last 45,000, 60,000 years ago.

IRA FLATOW: Any of these discoveries or anything new that we’re talking about in the world of Neanderthals give us any idea, get us closer to why they died out and we didn’t?

CHRISTIAN TRYON: I don’t know. I mean, for me, this is the million dollar question. As an archaeologist, of course, I want it to be something about behavior or things. This is what we study. And that may be, or it may be things about biology. It might be things about disease resistance, or frequency of birth, or child death rates. Things like this.

Or it might be that modern people figured out solutions to live in dense groups of people that weren’t related to them. They figured out ways to communicate with groups across space. We have some hints of this in the record about–

It’s a funny thing that archaeologists look at. They look at how far rocks people are transporting across the landscape and the stone tools they have. If you look at Neanderthals, they don’t seem to move these things very far, on average.

If you look at modern humans at the same time, on average, they’re moving these things over greater distances. And it implies these bigger social networks. They know people not just in the next valley, but they know people two, three valleys over.

And that’s useful in a situation where, if you’ve got a bad time, a bad year, you might know a big network of people you can tap into. You know, look, Joe, we helped you out two years ago, can you help us out now? And it may be that Neanderthals didn’t have that bigger social network to fall back on.

IRA FLATOW: Well, science loves a mystery and this will continue. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today. Chris Standish, archaeologist at the University of Southampton in UK. Christian Tryon, associate professor in the department of anthropology at Harvard University. Thank you all for taking time to be with us today.

CHRISTIAN TRYON: Thank you very much.

CHRISTOPHER STANDISH: Cheers.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Have a great weekend.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.