What Makes A Species Human?

11:28 minutes

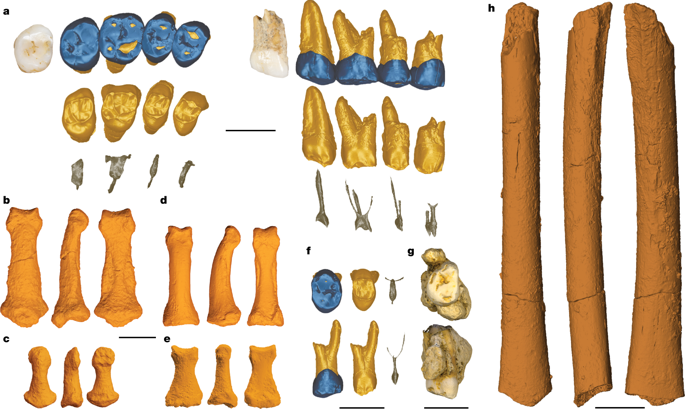

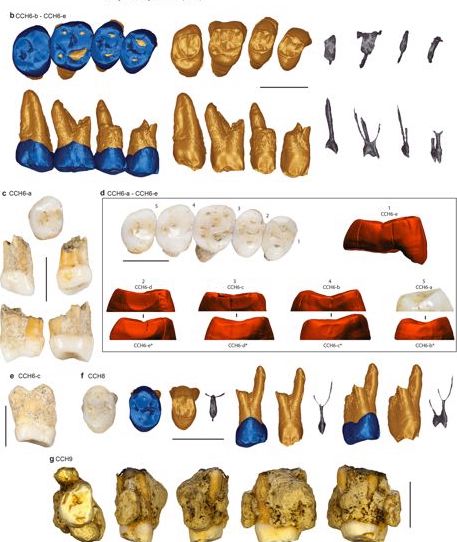

Last week, researchers announced they’d found the remains of a new species of ancient human on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. It was just a few teeth and bones from toes and hands, but they appeared to have a strange mix of ancient and modern human traits scientists had never seen before. Enter: Homo luzonesis.

However, Homo luzonesis’ entry on the hominid family tree is still fuzzy and uncertain. Paleoanthropologists have long debated which characteristics are necessary to determine a new species. Some fossils appear very different, but for others the differences can be much tougher to tell. Where do you draw the line, and add a new branch to the tree? Dr. Shara Bailey, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at New York University, joins Ira to weigh in on the new find and to discuss how we determine what makes a species “human.”

Shara Bailey is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at New York University in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, we’re going to take a look at the census. You know it’s happening next year. And so after you fill out the form, where does all that data go?

And we want to know, do you participate in the census? Are you curious about what happens to your data and how it gets used? Give us a call, our number 844-724-8255– that’s 844-SCI-TALK– or tweet us @scifri.

But first, last week researchers announced they found the remains of a new species of ancient human on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. It was just a few teeth, a toe, and hand bones, but they looked to have strange mix of ancient and modern human traits scientists have never seen before. So enter Homo luzonensis. Did I get that right, Shara?

SHARA BAILEY: Luzonensis, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Shara Bailey is Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at New York University. Welcome back to Science Friday.

SHARA BAILEY: Thanks. It’s so great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: OK. So have we now made the human family tree more complex now?

SHARA BAILEY: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah?

SHARA BAILEY: Absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: In what way?

SHARA BAILEY: Well, we’ve added another species. And not only that, but it’s a species that was living at the same time as we were. So it took a long time for us to accept Neanderthals as a separate species, and that coexisted with Homo sapiens, our species, and now we’ve got not only Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis, but Homo naledi and Homo floresiensis and now Homo luzonensis.

IRA FLATOW: So how do you decide where to draw the line about where it belongs?

SHARA BAILEY: Well, about where it belongs, like the relationship of that?

IRA FLATOW: Yes. Is it a human or non-human?

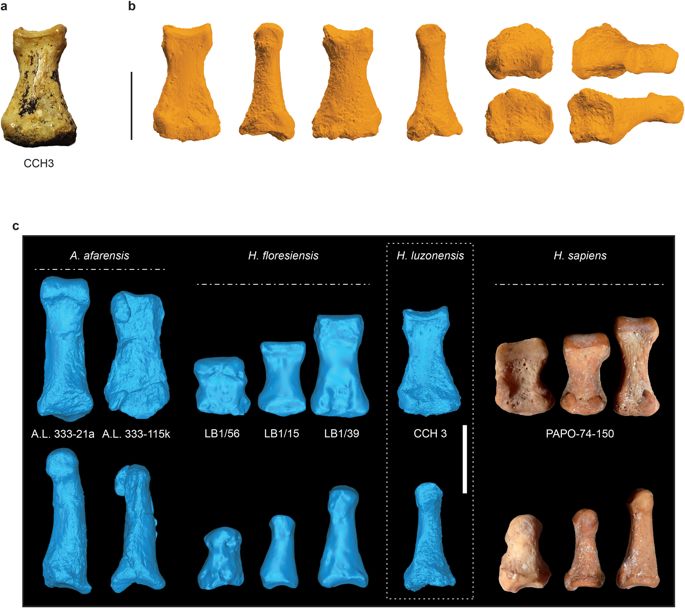

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, well it’s definitely human, right? So it has characteristics that align it much closer to humans than it does with apes. And even though it has some primitive characteristics, like the curved toe bone, for the most part, the majority of the characteristics align it with our genus, Homo.

IRA FLATOW: And so how many human-like, humanoids, hominids, are there out there or were there that we know about?

SHARA BAILEY: I think I could count them on two hands and a foot. I think maybe–

IRA FLATOW: That many?

SHARA BAILEY: –15. But maybe I’d need my other foot, too. I might need both feet. Yeah. It depends because there’s several species that are not accepted as widely as, let’s say, Homo floresiensis. So there’s Homo georgicus. There’s a number of other ones that people don’t talk about quite as much, but they’re out there. They’ve been proposed.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s talk about Homo luzonensis, where it lived and why it’s very similar to this other species, right?

SHARA BAILEY: To which one, floresiensis?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah. Well, I mean, they hypothesize– see, the problem is that Homo floresiensis is a lot more preserved. It has a skull, and it has two jaw bones, and it has a lot of postcrania, which are the bones underneath the head.

With luzonensis, you have a couple hand bones, a foot bone, a little piece, I think, of the thigh bone, and some teeth, and so we don’t know what its skull looked like. We don’t know if it was as small brained as floresiensis was, which is one of the things that made Homo floresiensis so contentious to begin with because it had an ape-sized brain.

They have proposed that it’s small bodied, which would align it with Homo floresiensis because both would be, then, kind of a dwarfed species of human.

IRA FLATOW: Under 3 feet tall they were saying.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: That is small body.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah. But it’s not atypical for that to happen on islands.

IRA FLATOW: Would we know if they were related at all? Were they around at the same period?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, probably, because on both islands, Flores and Luzon, they have earlier occupations dating to between 600,000 or 700,000 years ago that suggests that the ancestors of these species, Homo luzonensis and Homo floresiensis, were probably living at the same time. And so I presume that they would have evolved kind of in parallel to one another.

But they were on different islands, and so they would have acquired some similarities. Maybe the dwarfism is similar. But then the details could be different, especially if they weren’t interacting with one another.

IRA FLATOW: We talked about the bones. But also on the site, there were also some teeth. I know you’re an expert in ancient teeth.

SHARA BAILEY: Love teeth.

IRA FLATOW: So let me chew on that. You haven’t heard that one before, I’m sure. Was there anything curious about the teeth that the researchers found on the site?

SHARA BAILEY: Well, in many ways, they’re similar to Homo floresiensis in that they’re quite small. And the teeth get smaller towards the back of the tooth row, which is something that you see with Homo sapiens. And the morphology is quite simple, which is something that you see with Homo sapiens.

But the cautionary note is that there are other species. Now, there’s some fossils from Spain, Sima de los Huesos, now known to be Homo heidelbergensis or something related to Neanderthals that were, when they only had the teeth, they thought– and because they were small, they thought that it had to be Homo sapiens. So tooth size is actually very evolvable.

So they have quite small teeth that kind of align them with Homo sapiens. They have some very primitive features. So premolar roots– premolars are your bicuspids. The upper premolars should have one root, maybe two, and these have three.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

SHARA BAILEY: Or I might have gotten that wrong, but they have two very divergent roots– sorry, I’m blowing that. But when I look at the premolar, which is quite primitive looking, it looks a lot like some material I’ve seen in China that recently came out that they were kind of like, we don’t know what to do with this. So it’s very possible that that ancestor is on the mainland.

IRA FLATOW: Now, how do we know or how do we think that they– you spoke about the mainland being their ancestors. How did they get to the island? I mean, what drives them? And–

SHARA BAILEY: I don’t think they were–

IRA FLATOW: The dwarf ones to the island–

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, I don’t think they were necessarily driven. I think that their ancestors probably got to the island hundreds of thousands of years before these species that we’re picking up now. It could be that they were blown off shore with some kind of storm, and–

IRA FLATOW: It’s not something that they may have commuted back and forth.

SHARA BAILEY: No. And I– no, I don’t think so because–

IRA FLATOW: How far apart are we talking?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, I’d have to look that up.

IRA FLATOW: Tens of miles?

SHARA BAILEY: No, no, farther.

IRA FLATOW: Hundreds of miles?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, so much farther. You wouldn’t be doing any commuting. And if you were doing a lot of commuting, then I don’t think you would have had such strange morphology because there’d be gene flow going between populations rather than being isolated. But yeah, I think most of us would tend to think that they got there by accident.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think we’ll be able to find a skull–

SHARA BAILEY: I think so.

IRA FLATOW: –if they search long enough and around there?

SHARA BAILEY: I hope so.

IRA FLATOW: Well, why not, right?

SHARA BAILEY: We need one. Yeah, we really do. As I think everybody can relate, we like to look at faces to see whether we recognize a face or head as being something similar to us or not, and so very important.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me about that. So it really is us just analyzing, visually, the connection.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, I think. I mean, I think that’s part of it.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. How about analyzing the DNA? Is there any DNA left in any of these bones?

SHARA BAILEY: No, because in tropical areas, or even temperate areas, DNA preservation is very poor. So the DNA degrades. And I mean, here’s the thing, though, because the technology, the DNA technology, in the past 10 years has increased exponentially– so perhaps in the next 10 years, they’ll be able to extract DNA. But at this point, they can’t.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think that Homo luzonensis is going to be one of the discoveries that gets debated a lot?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Does it belong? Does it not? Where to put it?

SHARA BAILEY: I think– well, what it’s prompting me to do is to really think about how we define species, how much variability there is within species. I’m hoping that it actually makes more than just me, but other people, too, start really thinking about this and re-evaluating our paradigms, our theory.

IRA FLATOW: Would you like to be over there, taking it up?

SHARA BAILEY: Oh yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. My friend Matt Tocheri invited me over to see Liang Bua where floresiensis is. So I could always just pop on over there, too.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think if you have floresiensis and you also have this one, luzonensis, there might be a third, a fourth, the fifth?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah. And then we have to start really thinking about, are we going to really name all these different species, or are they variants of one thing? Do you know what I mean?

IRA FLATOW: Tell me, what do you mean?

SHARA BAILEY: So perhaps there is one ancestral species to all of those, and after they got to the island, they diverged in different ways, but they’re just dwarfed versions of this, whatever their ancestral species.

IRA FLATOW: And how would you decide that? What would make that as, you know–

SHARA BAILEY: Well, it would take a lot of debating within our community, but a lot more fossils and something that some traits that are shared uniquely between something on the mainland, let’s say, and then each one of those island populations.

IRA FLATOW: It was interesting because I saw the photos of the bones, and comparing the bone, how much it curved versus how straight it was, something as small as that, right? Whether it was a grasping finger bone or was it not?

SHARA BAILEY: Right.

IRA FLATOW: That’s sort of the– those sorts of minor things, to me, minor, decide where you place them.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, because it tells us something about their locomotion. But one thing that’s never been done, at least not that I know of– I don’t know that people have examined curvature in bones of humans who do a lot of climbing, or– humans can climb trees, and–

IRA FLATOW: I like that.

SHARA BAILEY: And the thing is–

IRA FLATOW: You’re even muddying the waters more.

SHARA BAILEY: I love to do that. But the toe bones and the finger bones– bone is dynamic. It responds to you.

IRA FLATOW: It’s alive.

SHARA BAILEY: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

SHARA BAILEY: As you know– and it responds to you. So see-

IRA FLATOW: So maybe they’re the same, except this one liked to climb a tree a little more, and so it developed a little more of a curvature.

SHARA BAILEY: Maybe they had to climb trees for their food all the time. I don’t know. I’m really stretching it here, but I think the cool thing about discoveries like this is it makes us think about new hypotheses, and somebody out there is going to go test that, or test other hypotheses, and that’s how science moves forward, as you know.

IRA FLATOW: But very slowly.

SHARA BAILEY: Unfortunately.

IRA FLATOW: Because if you come up with a new idea, you have to have good evidence.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: So you need to go out and find some more of these bones and teeth.

SHARA BAILEY: Yep, yep. That’ll help. I’m not sure it’s going to resolve it.

IRA FLATOW: Well, you’ll come back and talk about it if they find some more stuff, right?

SHARA BAILEY: Of course.

IRA FLATOW: All right.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very much. Shara Bailey is Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at New York University. Thank you–

SHARA BAILEY: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: –for taking time to be with us today.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.