You Aren’t Alone In Grieving The Climate Crisis

33:54 minutes

This story is part of Degrees Of Change, a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here.

This story is part of Degrees Of Change, a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here.

As the consequences of unchecked climate change come into sharper focus—wildfires in the Amazon and Australia, rising seas in low-lying Pacific Islands, mass coral bleaching around the world—what is to be done about the emotional devastation that people feel as a result?

In 2007, Australian eco-philosopher Glenn Albrecht described this feeling as homesickness “for a home that no longer exists,” which he called “solastalgia.” Others have settled on terms like “climate grief,” or, since environmental devastation can come without a changing climate, simply “ecological grief.”

For this chapter of Degrees of Change, Ira talks about adapting emotionally to climate change. First, he speaks with psychologist Renee Lertzman and public health geographer Ashlee Cunsolo about their research on the phenomenon of grief tied to environmental loss, and what they’ve learned about how people can adapt their grief into actions that can make a difference. Then, climate researcher Kate Marvel and essayist Mary Annaïse Heglar share their experiences simultaneously working on climate change, and grieving it.

Many of you used our Voxpop app to tell us how climate grief was impacting you.

Ariel: So, I’m awake at 4 a.m. And since having a baby, my level of anxiety has really intensified. I have so much fear for the future that we’re providing the next generation. Paula: Climate change makes me sad. Matt: I think climate change mostly makes me feel angry. Brook: Climate change makes me feel overwhelmed. There are so many changes to make that are not within my power. Morgan: I don’t understand why our politicians aren’t making this the highest priority. Alex: Will I even be able to retire? Jane: I think about it every single day. Craig: My son, who’s in sixth grade, has been learning about climate change and pollution. He’s been displaying a lot of anxiety about the topics and been asking a lot of questions like, “why can’t people just stop polluting?” But the enormity of the problem weighs heavily on him. Desiree: I do not want my students to feel discouraged. Sue: Now, I think we are past the point of no return. And now, it just makes me so, so sad. Jürgen: How am I handling it? I’m not.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, marine biologist, founder and CEO of Ocean Collectiv, a consulting firm for climate solutions. She’s also a co-signer of a Green Stimulus proposal for recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic:

“My job on this planet is to make things better. I can’t fix it, no one can stop climate change. That ship has sailed. But we have a lot of control over how bad it gets collectively and what is the role that I can play in being a part of the solutions—and we have so many climate solutions. I think people forget about that. We basically have all the solutions we need already. And so that’s what I keep coming back to is how can we accelerate all these solutions: regenerative farming on land and in the ocean and offshore renewable energy and restoring ecosystems that protect us from storms and absorb carbon on the coastlines, all those wetlands and mangroves and seagrass and oyster reefs.”

Meehan Crist, writer-in-residence in Biological Sciences at Columbia University:

“I think about this because my parents live in California and I watched them have to evacuate and be threatened by fire multiple times. And I’ve also watched the landscape of my childhood burning. And so the thing is—but it’s still there. I can still go to California. I can still see those oak trees, you still see golden hills. But I also know that probably it’s gone or going or going-ish, but I don’t know how quickly. So it’s still present, but it’s slowly disappearing and how do you mourn? How do you mourn the loss of someone whose hand you can still hold?”

Tara Houska, indigenous rights activist, Bear Clan Anishinaabe, founder of the Ginew Collective. She is organizing against Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline:

“We are people who came to this place because the food grows on water here. So it’s wild rice. That’s the heart of our culture and our identity. Because of climate crisis, and because of water quality changes and continuing pressures through fossil fuel infrastructure, projects, mining, all kinds of extractive industry, there are already lakes that are completely void of wild rice. There are already lakes that have warmed up or changed the ecosystem enough that that plant cannot survive. That is very frightening. That is the wiping out of the culture. So that’s an entire culture of a people’s identity. That is deeply, deeply sad.

Emily Atkin, journalist and creator of the Heated newsletter and podcast:

“What I effectively channeled with climate change to get me out of my grief state for it was realizing that there was a better way to tell that story and that there was an effective way to tell that story. And it was through anger, and it was through injustice. And it was through showing other people that they didn’t have to be sad, that there was another option for them. That this wasn’t something that was just happening to them, that it was being done to them.”

Daniela Molnar, artist. Read an article in the LA Times about her journey with climate grief and documenting it through art:

“Grief is very close to love. And if you allow yourself to feel grief, then you can—we feel grief because we feel love. And I think the two sort of interchange throughout the process. So I wouldn’t say that I’ve worked through it and I’m out the other end and I don’t feel grief. It’s an ongoing thing that I think that I will always be in, frankly. But the kind of grief that stops you and disallows forward momentum, and sort of contracts any other awareness of the world—I have moved through that.

Sherri Mitchell, indigenous rights lawyer and environmental justice activist, Penobscot Nation. Executive Director of the Land Peace Foundation:

“The division that we’ve created between us and all other living beings is melting away, the more that we cause this destruction of the natural world. And what we’re really experiencing when we’re driving down the road, and we’re suddenly overwhelmed with feelings of immense grief is the grief of the mother whale who is carrying her baby around for 17 days, trying to show us what we’re doing to their ecosystem. When we’re waking up in the middle of the night in a panic, we’re having the experience of the trees as they’re being burned down and logged, and (when we’re) feeling incredibly lonely, even amidst those that we love the most and who we feel deeply connected to, we’re sharing the experience of the last white rhino on the planet who has nobody left in their species to connect with.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Renee Lertzman is a psychologist and the author of Environmental Melancholia: Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement. She’s based in Marin County, California.

Ashlee Cunsolo is a public health geographer and the director of the Labrador Institute at Memorial University in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

Mary Annnaïse Heglar is the co-host of the Hot Take podcast and a writer-in-residence at the Earth Institute of Columbia University in New York, New York.

Kate Marvel is an associate research scientist at Columbia University and the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[PEACEFUL MUSIC]

[WAVES CRASHING]

[CLOCK TICKING]

In our latest chapter of “Degrees of Change,” climate change is rewriting the landscape of our planet, but also of our minds. When rising seas and wildfires displace people from their homes, when new species of animals and plants disappear from Earth, these abrupt changes pose a challenge to our emotional stability.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

When Australian eco-philosopher Glenn Albrecht described a unique sense of loss in people whose rural home had been completely transformed by strip mining, he coined the term solastalgia, comparing it to homesickness.

GLENN ALBRECHT: The critical difference was that these people were still at home. And it was quite clear to me that they were experiencing melancholia, distress. The key thing that they were missing from their home environment was the solace. So they felt as if their home environment was moving away from them. So solastalgia was created by me to describe the lived experience of negative environmental change. And the bumper sticker version of it was the homesickness you have when you’re still at home.

IRA FLATOW: The American Psychological Association acknowledges the mental health burden that can be imposed by climate change. It issues guidance to professionals who support individuals and communities grappling with climate grief and anxiety. Our listeners shared their feelings about climate change on the Science Friday VoxPop App.

ARIEL: So I’m awake at 4:00 AM. Since having a baby, my level of anxiety has really intensified. I have so much fear for the future that we’re providing the next generation.

PAULA: Climate change makes me sad.

MATT: I think climate change mostly makes me feel angry.

BROOKE: Climate change makes me feel overwhelmed. There are so many changes to make that are not within my power.

MORGAN: I don’t understand why our politicians aren’t making this the highest priority.

ALEX: Will I even be able to retire?

JANE: I think about it every single day.

CRAIG: My son, who is in sixth grade, has been learning about climate change and pollution. He’s been displaying a lot of anxiety about the topics and been asking a lot of questions, like, why can’t people just stop polluting? But the enormity of the problem weighs heavily on him.

DESIREE: I do not want my students to feel discouraged.

SUE: Now I think we are past the point of no return. And now it just makes me so, so sad.

JURGEN: How am I handling it? I’m not.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks to Ariel, Paula, Matt, Brooke, Morgan, Alex, Jane, Craig, Desiree, Sue, and Jurgen, who contributed their thoughts on the Science Friday VoxPop App. For this episode of “Degrees of Change,” we wanted to explore what it means to adapt not by building seawalls or planting trees, but by working through your feelings. So joining me today, please welcome psychologist Renee Lertzman, a founding member of the Climate Psychology Alliance and author of Environmental Melancholia– Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement. She joins us from Marin County, California. Welcome to Science Friday.

RENEE LERTZMAN: Hi, happy to be here.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. And also, Dr. Ashlee Cunsolo, a public health geographer and Director of the Labrador Institute at Memorial University . Her book is Mourning Nature– Hope at the Heart of Ecological Grief and Loss. She joins us from Happy Valley-Goose Bay in the Canadian province of Labrador. Welcome to Science Friday.

ASHLEE CUNSOLO: Thanks for having me, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Let me begin with you, Dr. Lertzman. Why is climate change causing people to feel grief and anxiety?

RENEE LERTZMAN: Well, when we think about climate change, it’s really often about loss, loss of specific creatures and species, loss of ways of life, of being. And I think more and more people are starting to experience what feels like grief, what feels like a sense of mourning.

IRA FLATOW: So is grief, though, the right word for something that isn’t dead, like a loved person?

RENEE LERTZMAN: I think that’s a really important question. And the way that the psychological field for so many years has conceptualized and understood grief has often been in the context of death of loved ones. And so there’s understandably some questions around, well, is this the same thing? And my response would be yes and. It’s not quite the same, but it’s in that same continuum.

IRA FLATOW: Ashlee, your work has not focused solely on climate change, but on something called ecological grief. What’s different about ecological grief?

ASHLEE CUNSOLO: Well, ecological grief is really similar to climate grief and to what Renee has been describing. The term ecological expands it to other forms of disruption that are, you know, human-induced, things like mining, and how that impacts an environment or an ecosystem. So it’s looking at the work by Glenn Albrecht and solastalgia. It’s looking at climate grief and anxiety. And it’s also understanding the other forms of environmental change that people can experience.

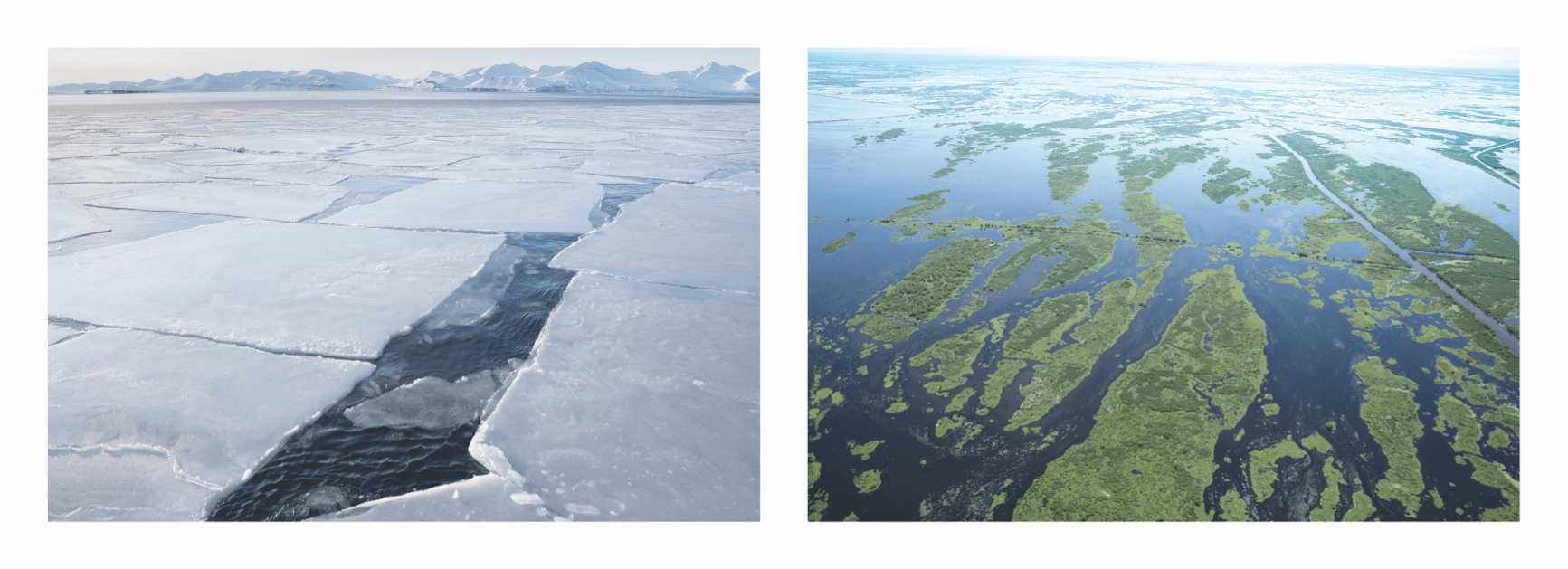

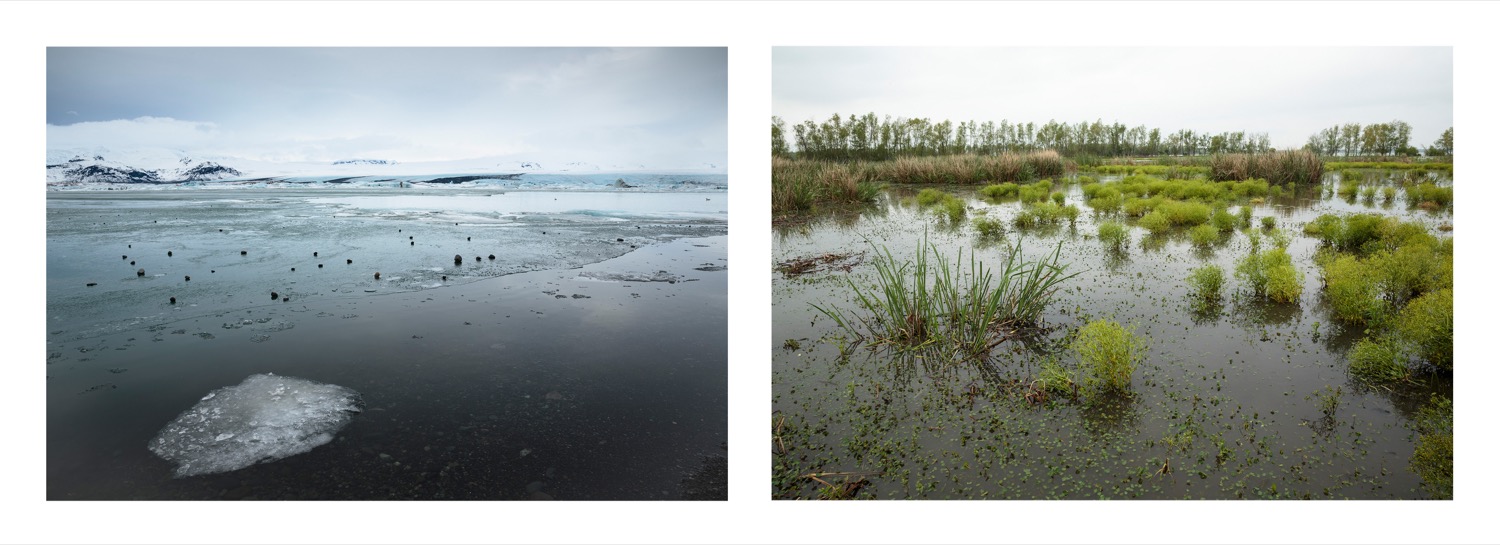

So climate grief is well within ecological grief. And part of the reason why I use that term is it really emerged from people that I was working with in northern Labrador, where they were describing sort of feeling a part of this larger ecosystem and being people of the sea ice and, you know, being so deeply connected to this more holistic understanding that climate was a part of, but it was shifting everything.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, tell us a little bit more about that, the Inuit people in Labrador. What were they grieving specifically about? What did they lose?

ASHLEE CUNSOLO: Well, for over 10 years, we’ve been working with five Inuit communities on the north coast of Labrador. And so these are people who have been there for thousands of years, connected to the land, the snow, the sea ice, the plants, the animals, everything. Everything comes from the land, and people feel deeply connected.

Labrador is also one of the fastest warming places anywhere in the world. And so that’s led to huge shifts in average warming temperatures. It’s led to huge declines in sea ice and really impacting people on all different levels– so the inability to travel to hunt and provide for family, increased family stress, a lot of fear and anxiety about what the future is going to bring. And in particular, a lot of people described a whole range of mental health challenges from climate change.

So grieving that, that melting sea ice, and that declining stable ice conditions that last for eight months of the year, grieving what it means for families as cultural patterns are shifting. So it’s things that have been lost. It’s things that are currently in process of being lost. And it’s also an anticipatory grief, where people think about, what’s it going to be like in five years or 10 years, in 20 years? And what does it mean for themselves, their families, their children, their grandchildren? And what does it mean to be Inuit in a time where environments are changing so much?

IRA FLATOW: Mhm. Renee, let’s again look psychologically at grief. How do you define grief? Is it a process people can complete and then move on from?

RENEE LERTZMAN: Well, actually, there’s different models of grief. So the most popular and well-known model is Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’ five stages of grief. There’s other models of grief that I find much more helpful for our work on climate change and environmental issues that are more dynamic. So I would align with the view that it never ends, it’s ongoing, and it has various kind of ebbs and flows to it.

I was very inspired by the work of British psychologist Rosemary Randall. And she talks about the work of William Worden, another British psychologist, where he talks about grief as tasks. And those tasks tend to involve, you know, the acceptance of reality and working through the painful emotions of grief.

And on the other side of these tasks are what happens when we sort of refuse them. It looks like denial, right? We shut our feelings down. We bargain and become maybe kind of techno-optimists. Or we might become sort of bitter, angry, depressed, and kind of just refuse to engage with the issue at all.

And so with all of these tasks we have choices. What’s incredibly important to emphasize is that grieving and mourning are social practices. We sort of need each other to be able to talk about these things and normalize that. And that’s the most powerful way that we can move through the grief in ways that are really creative and constructive and support our capacities.

IRA FLATOW: Ashlee, how have the people you’ve worked with adapted and moved through their grief?

ASHLEE CUNSOLO: Well, I think all the processes and tasks that Renee just described align so well with what people have been doing and what we’ve been talking about for years here. And I think one of the biggest pieces is that social piece and being able to talk about it.

You know, when we first started working on the research, and there is Inuit people who were doing the interviews and working with their fellow community members, and the conversations were the first time that people had actually vocalized their grief to each other. And so that started off this whole other process of people being able to name it and talk about it and start to find community and support and solidarity and knowing they weren’t alone. And so many people have said, “You know, I thought I was the only one that felt this way.”

But communities have also been trying to find ways to support cultural connection and cultural resurgence within communities, so that if people are unable to travel on the land because the ice hasn’t formed yet, what are the things that can be done intergenerationally in town? So more language classes– you’re seeing a lot of sewing and crafting happening, you know, people setting up woodsheds to work together, a lot of working through things by doing things.

IRA FLATOW: At least in the US, mental health is hard enough to get help with, and it’s not exactly something we’re encouraged to talk about. So how do we move toward offering people meaningful mental health support about something as politically fraught as climate change?

RENEE LERTZMAN: Right. Well, we’re seeing right now some transformation happening in the psychological field, in the mental health field itself, which has, in my view, been quite slow to really orient around what we’re talking about in these realities. But it is happening.

There’s a number of psychologists who are really working sort of from the inside out within the mental health field, because unfortunately, what can happen is people will seek out mental health support from a psychologist or a mental health professional who may not be sort of aligned or there yet. So that is happening. I think it’s very important when we seek mental health support to do that kind of vetting. Are they going to, you know, be on this wavelength and understand what it is we’re bringing and talking about is one piece.

And the other relates to social-cultural forms of support, right? So we’re seeing the Good Grief Network. We’re seeing initiatives. We’re looking at community responses, as Ashlee’s describing, that actually provide a tremendous amount of what we would call mental health support by creating spaces where people can come together and talk about what they’re feeling and be able to process that in a safe environment.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re talking about climate grief with psychologist Renee Lertzman and public health geographer Ashlee Cunsolo. Ashlee, one example of collective grief that I saw recently this year were– it was the wildfires in Australia, and before that, the Amazon. They captured the public imagination and sadness in a way that I haven’t seen in a long time. What happens when a large number of people all grieve the same occurrences this way?

ASHLEE CUNSOLO: I think, in many ways, that’s been a huge shift for understanding large-scale, collective grieving. So we talked about anticipatory grief, but there’s also sort of vicarious grief, where just your capacity to be empathetic and compassionate and care for others, that even if you’re not in Australia experiencing the fires, you can see the devastation. And people were openly sharing their pain, their grief, their fear, their sadness, their disbelief.

The testimonies that were coming out of Australia– everything kind of compiled together to tell this very strong, collective, human story where people were really starting to very explicitly talk about grief related to climate and environment and very explicitly link it to climate change. Even in government policy discussions that I was in, it was starting to come up a lot more. And I think that type of collective solidarity of actually discussing and beginning to normalize grief related to the environment was a huge step forward.

And I know, particularly in Labrador, where these conversations have been happening, and other parts of the north, where people have been experiencing these long-term changes already, that sense of, like, knowing what people were feeling and knowing what that loss meant and that sort of, you know, experiential, collective solidarity was really powerful as well.

RENEE LERTZMAN: So something really important when we’re talking about grief is the tendency we have to assume that it’s a negative and that it’s a downer. And listeners might be already kind of a little scared of this episode, that it’s going to bring me down.

And it’s so important to recognize that the more we can really talk about this and share how we’re feeling, it has the paradoxical effect that it gives us wind in our sails, that it really allows us to access more creativity and energy that we’re needing, precisely in times like this. It’s actually the way to come out of the hole, is by naming it and talking about it.

ASHLEE CUNSOLO: I completely agree with that. I mean, this grief related to environmental change is– we should understand it as something so normal and natural and not pathological and not something to be afraid of, something that can actually be an opportunity, a doorway to walk through, where we understand we have capacity to make change, because we only grieve what we love.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, actually very interesting and nice to hear. All right. In the moment I have left, some quick advice for people, you know, who are grieving, overwhelmed emotionally. What do you tell them to do? Where should we send them? How can they get help?

RENEE LERTZMAN: Well, the first thing I would suggest is to accept and have compassion and kindness for what we are experiencing, you know, starting just there. And second is seeking out and connecting with others with whom you feel you can be safe and yourself with and can really share what’s coming up for you and to listen to others. So really, that social interaction, that relationship piece is so, so vital right now.

And the third is, you know, I would encourage people who are interested in seeking professional support, counseling therapy, groups, to explore that, you know, to recognize that there are resources available for us and that we’re not in this alone.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting and useful advice, I think, to people who need some help, because we all, you know, need some help these days, from grief in two different directions. That’s good to know. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today, psychologist Renee Lertzman, author of Environmental Melancholia– Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement– she was joining us from Marin County, California– and Dr. Ashley Cunsolo, a public health geographer, Director of the Labrador Institute at Memorial University in Happy Valley-Goose Bay in Labrador. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

ASHLEE CUNSOLO: Thanks so much, Ira.

RENEE LERTZMAN: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. We have more resources and stories from scientists and others about their climate grief up there on our website at sciencefriday.com/grief. After the break, what happens when you’re a climate scientist or a climate activist, and you’re facing down your own climate grief and anxiety? We’ll talk about studying and fighting climate change without getting stuck in despair. This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[PEACEFUL MUSIC]

[WAVES CRASHING]

[CLOCK TICKING]

In this episode of “Degrees of Change,” we’re talking about a different kind of climate change adaptation, the emotional adaptation, understanding and accepting the kinds of profound changes and losses that the world is experiencing as seas rise, fires rage, and rain relocates.

In our last segment, we talked with people who research this landscape of climate and ecological grief. But what about the people whose work centers on understanding and describing the realities of climate change, the scientists, the journalists, the activists? How do they grapple with grief while staring at the depressing data every single day? Producer Christie Taylor spoke to several people who fall under this umbrella, and here is some of what they had to say.

AYANA ELIZABETH JOHNSON: It sucks. It sucks to know this much about what’s coming and how much of it is already guaranteed. And I, you know, I cry. And a lot of people are going to get hurt, and a lot of people are going to die, and a lot of the ecosystem and species that I love are going to be unrecognizable or gone.

MEEHAN CRIST: A new IPCC report will come out, and, you know, it’ll kind of all come flooding up. And you’ll just think, “Oh, God, I knew it was bad, but it’s really bad.”

TINA FREEMAN: And then when the whole Katrina came along, that was enormous, the grief, the PTSD of the entire city.

TARA HOUSKA: There are already lakes that are completely void of wild rice. That’s an entire culture of a people, identity of a people. That is deeply, deeply sad.

DANIELA MOLNAR: I couldn’t possibly absorb it all. And if I could possibly absorb it all, there was no way that I could possibly act.

EMILY ATKIN: And I think that once you realize, in any situation where you’re sad, that it’s not your fault or it’s not happening to you, but someone’s doing it to you for no reason, it sort of changes the way you feel about it.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks to Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, Meehan Crist, Tina Freeman, Tara Houska, Daniela Molnar, and Emily Atkin. And now to talk about further staring at the face of our climate crisis every day and moving through the grief, let me introduce my guests, Dr. Kate Marvel, a climate researcher and research associate for Columbia University and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and Mary Annaise Heglar, co-host of the Hot Take podcast, writer-in-residence for Columbia University’s Earth Institute.

Kate, let me begin with you. You’re a climate scientist. You know the data. You look at the models. You understand their implications. What is it like emotionally for you?

KATE MARVEL: I sometimes feel like there should be– and there probably is in German– a word that captures the feeling of being simultaneously really excited to find out something new but then really depressed when you realize its implications. And whatever the word for that is, I feel that almost every day.

IRA FLATOW: Hm. Do you find that other scientists often talk about the emotional reaction they’ve had to understanding and researching climate change?

KATE MARVEL: I think more and more. I think for a long time, there’s been this notion that there is no place for emotion in science. You have to be cold. You have to be objective. And obviously, it’s not very scientific to pretend that something doesn’t exist just because it might be inconvenient. So I think there’s now more researchers feeling more comfortable talking about their emotional reaction, because we’re all living here. We all live on this planet, and it’s this planet that’s changing really rapidly.

IRA FLATOW: Mary, you write in one of your essays that “every climate person has a moment when climate change breaks their heart.” What was yours?

MARY ANNAISE HEGLAR: So I kind of came to this, like, really realizing how serious it was around 2014, when I joined one of the big green groups, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and my job was to edit policy reports. And those things are really scary if you edit them well, because that means you need to interrogate every sentence and, like, really understand what it means. And if you do that, you start to see all the lives that hang in the balance between the lines. And that’s terrifying.

And so there were so many times where I would call up the authors and be like, “Wait, is this– am I reading this right?” And there were a couple of the reports on, like– like pipelines, for example, really, really scared me and would send me into, like, different little waves of shock. So I think the whole year of 2014 was my heartbreak moment.

IRA FLATOW: In our last segment, we really drilled into how people feel grief about changing climate. Is this the word you would use? Let me ask both of you, do you feel grief?

MARY ANNAISE HEGLAR: I definitely feel grief, and I think the thing that is unique to climate grief is that, you know, you’re supposed to go through these different stages of anger and despair and shock and so on. And then you’re supposed to wind up at acceptance. You know, that’s what happens when you mourn a relationship or the death of a family member. You wind up at acceptance.

And with climate, you can’t accept it, because accepting it is not accepting, you know, this loss of something external to yourself. It’s the loss of everything that you love and everything that you need and even yourself. And so there’s no way to really, truly accept that. So you kind of just keep cycling through despair and anger and confusion and all of these different phases over and over again. But anger is a great place to be. Like, if you got to pick one to stay at, I would pick that one.

IRA FLATOW: Kate, would you go to anger or go to grief?

MARY ANNAISE HEGLAR: Well, I want to clarify that I think anger is part of grief.

KATE MARVEL: Yeah, I agree with Mary. I agree that it’s not possible to sort of cleanly separate out grief from all of the other emotions. For me, the most comfortable and maybe productive place to be is a sense of gratitude and wonder, knowing that this planet is so special. We don’t know of a single other planet in the entire universe that’s anywhere near as suitable for us and all the things we like to do. So for me, there’s that sense of real gratitude. But it’s always intermingled with sadness and fear and just fury, but hope and determination as well.

IRA FLATOW: We talked to a past guest, ocean scientist Dr. Ayana Johnson, about how she deals with her grief. And she said it’s about focusing on solutions and what she can do.

AYANA ELIZABETH JOHNSON: My job on this planet is to make things better. I can’t fix it. No one can stop climate change. That’s ship has sailed. But we have a lot of control over how bad it gets collectively, and, you know, what is a role that I can play in being a part of the solution?

IRA FLATOW: Kate, do you think working toward solutions is a good answer to your grief?

KATE MARVEL: I do, because I think what if– you know, imagine we didn’t know what was causing the climate to change. Imagine if this was something completely beyond our control. The helplessness and the anxiety and the fear that, I think, I would feel knowing that there’s nothing we can do, that would, I think, overwhelm me.

And so knowing from a scientific perspective– and I don’t at all want to minimize the social challenge ahead of us– but from a scientific perspective, we know exactly what’s causing the planet to get warmer, and we know exactly what we have to do in order to stop that.

IRA FLATOW: And Mary, from the point of view for people who aren’t scientists, how do you– can you use work also?

MARY ANNAISE HEGLAR: Absolutely. Everyone can. You do not need to be a scientist to be part of this or be part of the solution at all. As a matter of fact, if all we needed was scientists, like, it would have been solved, you know? They’ve been in agreement for a really long time.

And also, I’m not a journalist. I’m a writer. So I don’t do, like, investigative journalism. I didn’t go to journalism school or anything like that. So my writing is more from the perspective of a literary writer or a creative writer. And that means that I bring an air of art to writing. And I think the climate movement absolutely needs art. I think that we have to start seeing this less as some sort of scientific experiment and more as a social movement for justice. And there’s never been a social movement for justice that only had one type of person involved.

My best analogy is the civil rights movement. And there were artists. There were writers. There were organizers. There were some of everybody was involved, because it had to become– that was a fight for survival, and that meant it had to become part of who everyone was and part of their identity. And I think we need the exact same thing for climate.

IRA FLATOW: Mary, you wrote an essay for The New Republic where you directly compare climate grief to the emotional turmoil many are feeling right now as we isolate and witness the unfolding coronavirus pandemic, describing both as “tectonic shifts in the way the world works” and “the end of something big and precious and irreplaceable.” Please tell us more about that.

MARY ANNAISE HEGLAR: Yeah, I think, you know, the climate crisis and the corona crisis, in their own way, are both existential crises. They’re different in really fundamental ways. The corona crisis accelerated really fast. There was no reason it needed to get this bad. We definitely had enough warning to stop it from getting as bad as it did. But compared to climate, we really didn’t have that much of a warning. Like, there were decades of warnings about climate before it became, you know, part of our reality.

On the other hand, climate is more, like, slow moving, but it’s also permanent, whereas corona is likely temporary, and the big difference being that we have the solutions for climate, or we have a lot of them. And that means we just– that actually is very hopeful to me.

But there’s just no way of ignoring how different they’ve made the world that we operate in. There’s no other way of looking at this massive loss of life as anything other than a collective trauma that we’re all suffering through together. And you really don’t know what’s on the other side of them. But I think what makes them very similar is that what we absolutely need to be on the other side of them is compassion and empathy for one another.

IRA FLATOW: Mhm. Kate, we’re in the middle of a pandemic, of course. There are people who might ask, should we still be talking about climate change right now?

KATE MARVEL: I think absolutely. I think it’s a completely false dichotomy to separate out a pandemic from climate change, because they are both problems that we’re going to have to deal with. And I think one kind of illuminates the other, and it goes both ways. People, I understand, are desperate to return to something that feels like normal. But with, I think, both COVID and the climate crisis, I don’t think there is such a thing as business as usual.

With climate change, if our emissions continue along their current trajectory, we are going to live in a climate that’s unprecedented, that nobody has experienced. And so in order to cut those emissions, everything is going to have to change. And so I think there’s this real sense in both cases of really facing down that scary but also, ultimately, really energizing possibility that everything will have to change, or it will be changed for us.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. You know, I see a whole range of attitudes about climate change, even just on social media, from politicians. Some say they have a lot of hope, and we’ll engineer a way out of this. Others say, well, what’s the point? We’re doomed. Mary, where would you place yourself on that spectrum of hope and despair, and are these even the right words to consider?

MARY ANNAISE HEGLAR: I think that there is a lot of room between those two very, very big extremes, and I’m probably squarely in the middle. A great friend of mine named Kate Marvel wrote a masterful essay on, you know, what we need to face climate change is not hope, it’s courage. And I think that is a major motivator for me.

Hope is not the thing that gets me out of the bed every morning and makes me want to fight climate change. It’s courage. And it’s also a certain amount of spite at the fossil fuel industry and the people that got us into this mess, that I will not be pushed lightly into that good night.

I don’t think that we’re doomed. I also don’t think that there’s any case for, you know, blind hope, because to my mind, the thought of hope– hope is what you do when you can’t do anything else. Hope is, like, you hope someone else will deal with it. I’m too busy at work to worry about hope.

IRA FLATOW: Mhm. Kate Marvel, your name came up about courage. Tell us about that.

KATE MARVEL: I mean, I want to be clear that I’m not anti-hope. You know, I’ve had people say, “Oh, climate scientists lost hope.” And for me, it’s that it’s not really relevant. Or, I mean, I guess, to put it in a shorter way, make your own damn hope, you know? You need to go out, and you need to do the things that we know need to be done.

I think there is a danger in saying some miraculous technology will come along and save us, because we have miraculous technologies already, and it’s not– we just need to use them. We need to adopt them. And I think this is really important. And I want to go back to something that Mary said before, where climate change, we treat it like it’s a scientific issue. But it’s not just a scientific issue. And scientists, we can’t be the only parts of the solution here.

I see headlines all the time that say, “Scientists are worried about warming world. Scientists worried about climate change.” And I’m just thinking, what are the rest of you doing? How come everybody else isn’t worried, you know?

[MARY LAUGHS]

So, you know, I think this is something that we’re really going to have to tackle together. And it’s going to require a lot of humility on the part of scientists to recognize that we are a part of the solution, but we’re not the only part of the solution.

IRA FLATOW: I want to thank both of you. We’ve run out of time. Dr. Kate Marvel, climate researcher and research associate for Columbia University and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Mary Annaise Heglar, co-host of the Hot Take podcast, writer-in-residence for Columbia University’s Earth Institute, thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

KATE MARVEL: Thanks so much for having us.

MARY ANNAISE HEGLAR: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: I want to thank everyone again whose voices we heard talking about their relationship with climate grief. We have many of them collected on our website, plus resources for thinking about the environment and your emotions. They’re up there on our website at sciencefriday.com/grief.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.