Genetic Tests Reshape Bull Market For Beef Producers

4:43 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story, by Kristofor Husted, originally appeared on 91.3 KBIA in Columbia, Missouri.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story, by Kristofor Husted, originally appeared on 91.3 KBIA in Columbia, Missouri.

Beef cattle ranchers are getting wise to the science of genetics.

They have always known that making the best steak starts long before consumers pick out the right cut, or where an animal grazes or what it eats. The key is in the genetic makeup—or DNA—of the herd. And over the last year, those genetics have taken a historic leap thanks to new, predictive DNA technology.

This is playing out in rising auction prices for the best bulls as identified by genetic profiles or simply for their elite pedigree.

“The demand there is primarily because we have the best genetics in the world,” said Gordon Doak, president emeritus of the National Association of Animal Breeders.

Doak said the science is improving quickly.

“The bull (ranchers) used two years ago—they’re not going to use him again,” Doak said. “There’s new ones coming online all the time that have better genetics. That’s why (demand) has increased.”

Today, ranchers can shop for bulls or bull semen touting a very specific genetic concoction that’s prime for improving their herd. And those concoctions are becoming more valuable every day.

[These cartographers are mapping the journey of marine animal migrations.]

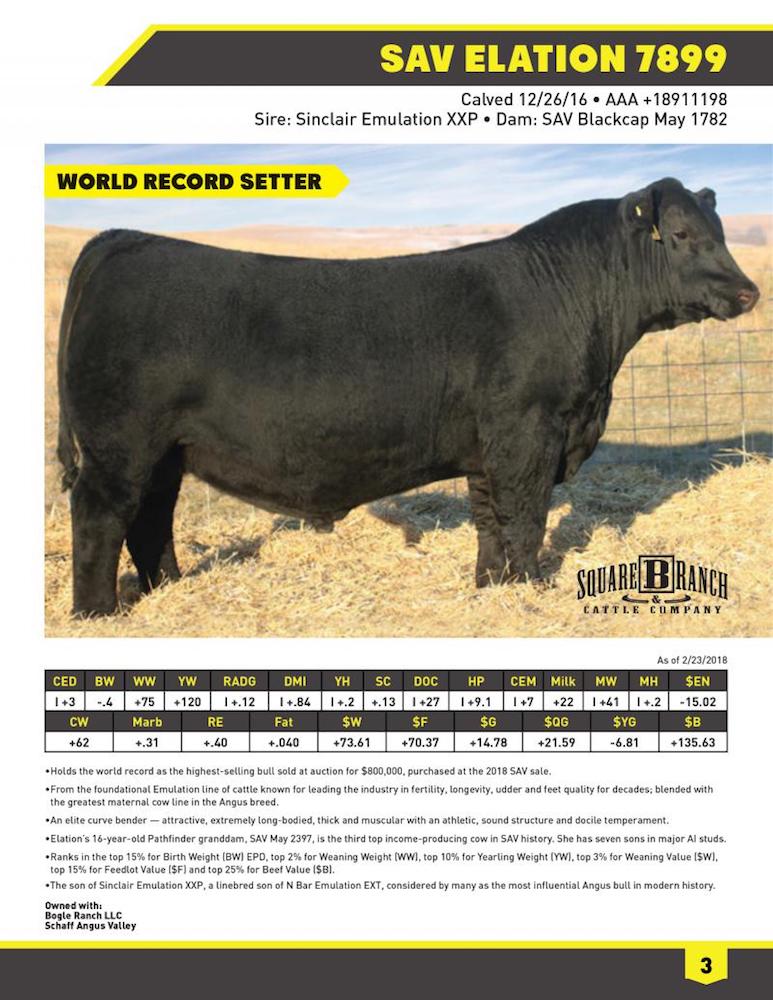

Missouri rancher Brian Bell traveled to North Dakota for a cattle auction in February. Like many of the hundreds of attendees, he had his eye on a specific Angus bull named Elation.

Elation, raised at Schaff Angus Valley in North Dakota, is descended from a famous family of beef cattle and has the genetic recipe for efficient, meat-producing cattle.

“Perfect footed. Perfect uttered. Fertile,” Bell said. “You know these cattle have some longevity and will stay in people’s herd and allow them to be profitable.”

Bell and Oklahoma rancher David Bogle teamed up so they could afford to bid on Elation.

“At the end there were three people bidding on the bull—one was from overseas and then two in the states,” Bell said. “And David jumped the last bid I think by $50,000. That was the deal sealer there.”

While some dairy cows have been auctioned for more than a million dollars, the final price for Elation—$800,000—set a world record for a bull.

“It’s an investment in our herds,” Bell said, adding: “And then also we’ll sell semen throughout the world and hopefully help pay for the bull.”

Yes, the semen.

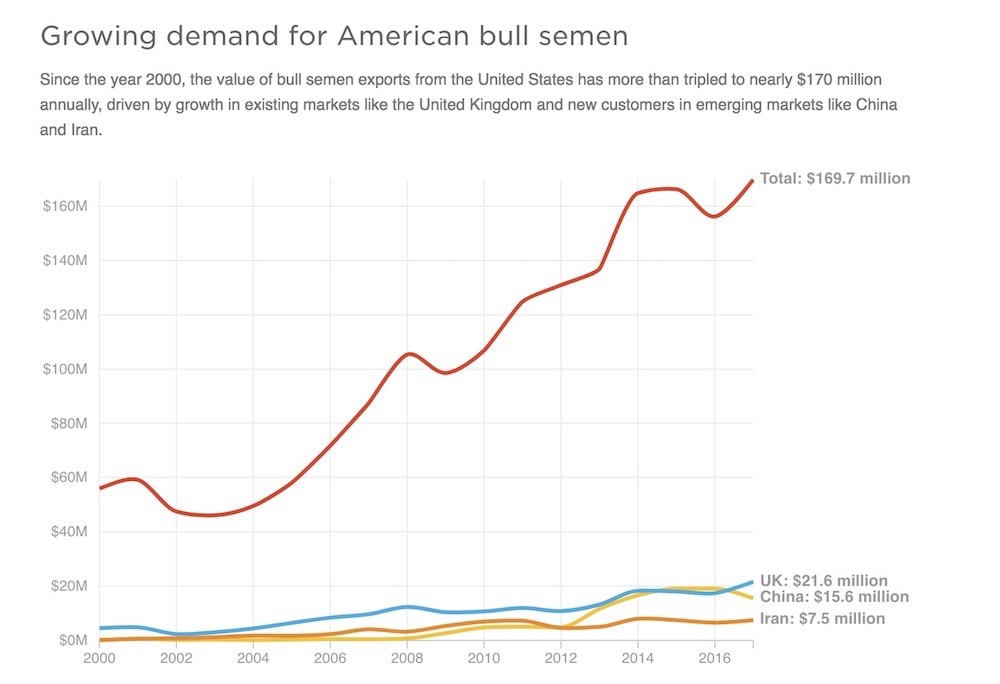

More than 2.5 million samples of beef semen were sold in the United States last year. That’s double from 2010, according to the National Association of Animal Breeders. Altogether, exports for dairy and beef cattle semen hit a record $170 million in 2017, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Census Bureau Foreign Trade data.

Bull semen is even sold on Amazon.

Brian Bell and David Bogle each hold 40 percent ownership of Elation, with 20 percent staying with Schaff Angus Valley.

And so far the investment is working out. While most Angus semen fetches $20 to $25 per sample (also called a straw), Elation’s semen is selling for $50.

Bell said they already have a waiting list from cattle ranchers across the world. As of April, Bell said he had already sold 4,500 straws and his investment in Elation could be paid off in one to three years, depending on how tasty Elation’s hundreds or even thousands of progeny turn out to be for beef customers.

That’s because he also plans to use Elation’s semen in about 450 of his own cows at Square B Ranch in Missouri.

“That’s the most important part because ultimately that’s our customer,” Bell said. “In the beef world, we’re trying to grow beef whether it’s at a high-end restaurant or they’re picking it out of the meat department at a grocery store.”

About 85 percent of U.S. beef ranchers, though, still develop herd genetics the old-fashioned way—by setting a bull loose with cows in a pasture, according to estimates by the National Association of Animal Breeders.

In buying those bulls, ranchers traditionally have analyzed how a prospective bull’s progeny developed over generations, using genetic predictions called Expected Progeny Differences or EPDs. That shifted in November, when the American Angus Association introduced a genomic testing kit that drills down into even more specific traits.

[How can abstract math analyze social injustice?]

For $37 a pop, ranchers can send a tissue or blood sample in and receive a readout on how that bull’s genetic makeup compares to others in the breed.

“Genomic testing allows us to basically find animals that are better for traits like marbling earlier that have a bigger tendency to pass down those traits later on in life as parents, so that we can create a better product for the consumer,” said Kelli Retallick, genetic services director for Angus Genetic Incorporated, the breeding arm of the American Angus Association.

Retallick said the association has 467,000 genomic profiles of cattle to reference when it analyzes a DNA sample. Researchers help narrow in on traits that indicate which bulls would produce the fastest growing calves? Which would produce the most fertile cows? Which would grow the biggest rib eyes?

This new tool was in evidence at a recent auction in Salisbury, Missouri, where about 100 people gathered to pore through the genetics of the 88 cattle up for sale. Each bull was DNA tested to see how it compared to others in the Angus breed. Next to each photo in the sales catalog is what looks like a baseball card that includes a bull’s birth date, weight and a chart of statistics from his DNA test.

When bulls were brought into the sales ring, the auctioneer yodeled out the results of his DNA test.

This new genetic information takes some of the risk out of the equation, said Jared Decker, a cattle geneticist and assistant professor at the University of Missouri.

“If we have a genomic-based, DNA-based genetic prediction, there’s less possibility for that genetic prediction to change as we get more data back on that animal,” he said. And that predictability cut costs for ranchers.

But for the DNA tests to be useful, ranchers have to benchmark their livestock with measurements and ultrasound scans that correspond to the DNA.

“If we’re not turning in those weights and if we don’t get that hard information or those scans, five years down the road, our DNA doesn’t mean anything to us because the DNA is changed. These animals have changed and evolve through selection pressure,” said Wes Tiemann, a cattle sales coordinator and producer from central Missouri.

Tiemann said he has more customers asking about the genomics of cattle for sale every week and expects that to continue with increased consumer demand for beef.

And that’s the final piece of the picture: Across the globe, people are hungry for quality beef.

“Consumer demand for all meats have been stronger both in the U.S. as well as the rest of the world,” University of Missouri agricultural economist Scott Brown said.

“I think consumers today are talking a lot more about the taste of meat products and have been willing to potentially add more meat to the diet than we’ve seen in the past,” he said. “And if that trend continues I think it bodes well for the livestock industry.”

[Bringing electronic health records into the modern age.]

The DNA tests are helping producers improve the U.S. beef herd strengths and fix its weaknesses, in the end creating a diner’s dream steak, Decker said. His research group is even working on tailored DNA tests that can better predict how productive cattle will be in specific environments with humidity, elevation, or toxic vegetation.

And at future cattle auctions, ranchers likely will have more traits available in each bull’s genomic profile for decision making.

Ultimately, whether a rancher is bidding for the first million dollar beef bull or examining a bull’s genomic readout, the U.S. beef herd’s genetic makeup is evolving.

And while these prized bulls will likely never meet many of their offspring, many shoppers will meet them in the grocery story as this pool of genetics shapes the beef herds in the U.S. and the international markets.

Kristofor Husted is a Harvest Public Media reporter based at KBIA in Columbia, Missouri.

IRA FLATOW: Now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: –St. Louis Public Radio–

SPEAKER 4: –Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national import– and when you choose a steak, there are a lot of factors to consider, right? Do you like yours medium or rare, T-bone or rib eye? But long before that steak gets to your plate, farmers and ranchers are making decisions of their own.

And increasingly, in the beef cattle world, these decisions are being shaped by genetic testing, with farmers selecting specific traits that they hope to see in future generations of cattle. Joining me now is Kristofor Husted. He’s Harvard’s– he’s Harvest Public Media reporter at KBIA in Columbia, Missouri. Welcome to the program.

KRISTOFOR HUSTED: Hey, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: So tell us about this new way. What sorts of genetic traits are beef producers looking for?

KRISTOFOR HUSTED: Right. There’s a lot– there’s a lot they’re looking at. One of the biggest ones is birth weight or weaning weight– things that farmers depend on. They want to know how quickly their cattle are going to grow. They’re also looking at how their rib eyes are developing, how much marbling is in their meat. So there’s a variety of things that they’re looking at.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And how does this work? Is there a– as you say, is there a catalog– that now I can choose my cattle? I can basically decide what steak I want to grow?

KRISTOFOR HUSTED: Essentially, yeah. You look at your herd. You look at what are its weaknesses. And then you can select the things that you want that can help strengthen your herd, whether you want to have cows that grow a lot faster or have higher feed efficiency. And those traits can get incorporated into your genetic pool in your herd and strengthen that, and ultimately help save farmers a lot of input costs.

IRA FLATOW: So what’s the– what’s been the drive behind this?

KRISTOFOR HUSTED: Right. So actually, a couple of years ago, in 2012, there was a big drop that took out a lot of the cattle inventory in the US. So people have been trying to build back their herds. And since then, genetic testing has also progressed. And this is a much more predictable way to pick and select what you want in your herd.

Not having to spend a ton of money trying to figure out if your cow is going to be better at eating grain versus hay versus grass, whatever it might be– it takes a lot of the gamble out for farmers. So you can put in a little more money on the front end to get your cow genetically tested so you know what more of those traits are going to be like in predictability.

IRA FLATOW: Is the science mature enough to really know how well– you know, you’re spending your money on this– how successful you’re going to be?

KRISTOFOR HUSTED: Right, you can’t rely completely on this just yet. It’s still just one tool in the tool box, as the cliche goes. But it is becoming more important because there are more traits that are getting tested. So there’s more DNA markers that scientists are looking at to help select for different types of traits that we don’t look at right now that could help farmers be even more specific and precise with what they’re looking to add to their herd.

IRA FLATOW: So I’m reminded of when we hear of horses– you know, champion horses. They go out to stud. They’re bred because they run really fast. This is the next step, it sounds like. You’re not– you’re not just looking at the– you know, the total horse, or the total cow, or the beef cattle here. You’re looking at a specific trait. I want a T-bone steak. I’m going to breed this for a T-bone steak.

KRISTOFOR HUSTED: Exactly, exactly. You, essentially, are going to be able to choose what type of meat. I mean, I’m sure there’ll be all around perfect general cow if you will. But there will be ones that have specific traits that are better for tri-tip versus a rib eye, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: So this is a big business. I mean, there must be international interest in this.

KRISTOFOR HUSTED: There is a lot. You know, we have developing economies in China and India, and with those growing middle classes, we have more people interested in buying beef. So a lot of interest is coming from overseas. And that’s driving a lot of the uptake in beef across the world, and mostly with American genetics. So in 2017, I think it was $170 million worth of bull semen was actually sold, exported out of the US. That’s triple in the past 20 years. So American genetics in beef, at least, is getting distributed all over the world.

IRA FLATOW: Well, speaking of butchering, forgive me for butchering your name, Kristofor. Kristofor Husted a Harvest Public Media reporter at KBIA in Columbia. Thanks for taking time to be with us today. And we have a story about beef genetic testing on our website at sciencefriday.com/bulls.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.