Into The Woods—For Birds!

16:11 minutes

This story is part of our winter Book Club conversation about Jennifer Ackerman’s book ‘The Genius of Birds.’ Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or send us your thoughts on the SciFri VoxPop app.

This story is part of our winter Book Club conversation about Jennifer Ackerman’s book ‘The Genius of Birds.’ Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or send us your thoughts on the SciFri VoxPop app.

The Science Friday Book Club is buckling down to read Jennifer Ackerman’s The Genius of Birds this summer. Meanwhile, it’s vacation season, and we want you to go out and appreciate some birds in the wild.

But for beginning birders, it may seem intimidating to find and identify feathered friends both near and far from home. Audubon experts Martha Harbison and Purbita Saha join guest host Molly Webster to share some advice. They explain how to identify birds by sight and by ear, some guides that can help, and tips on photographing your finds. Plus the highlights of summer birding: Shore bird migration is already underway, and baby birds are venturing out of the nest.

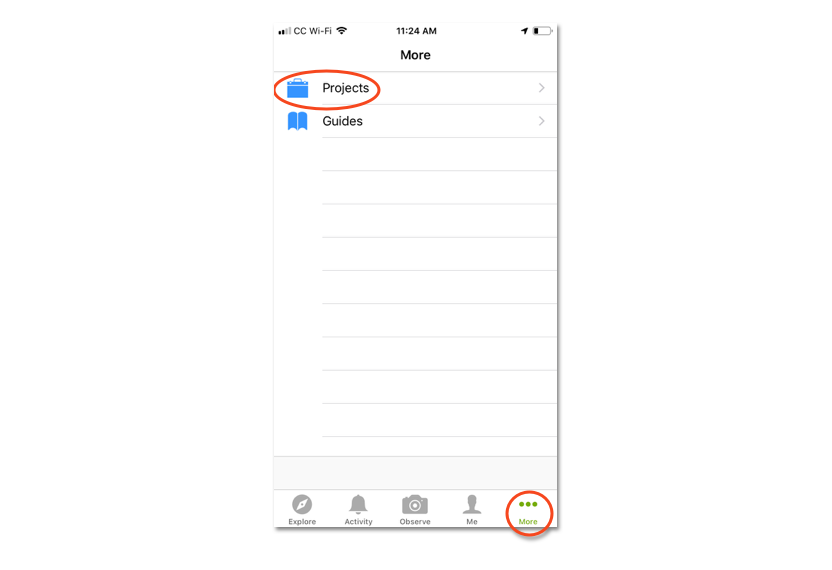

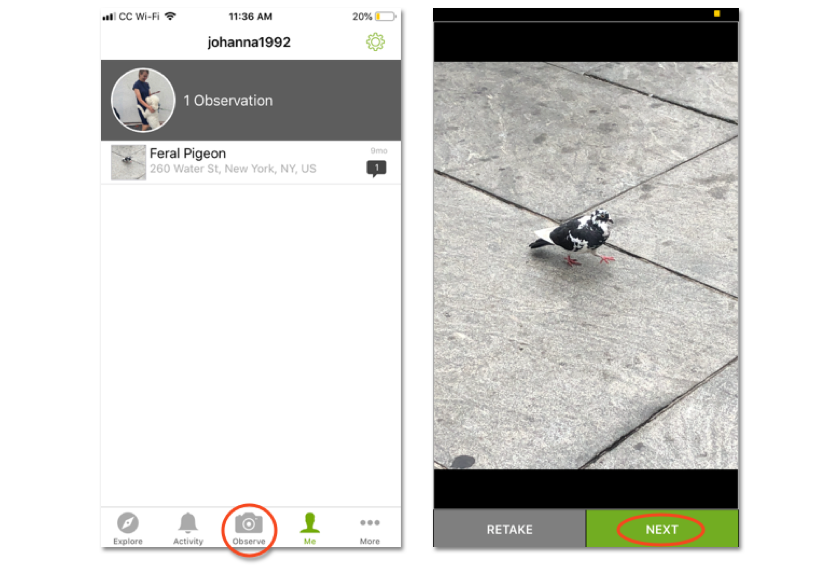

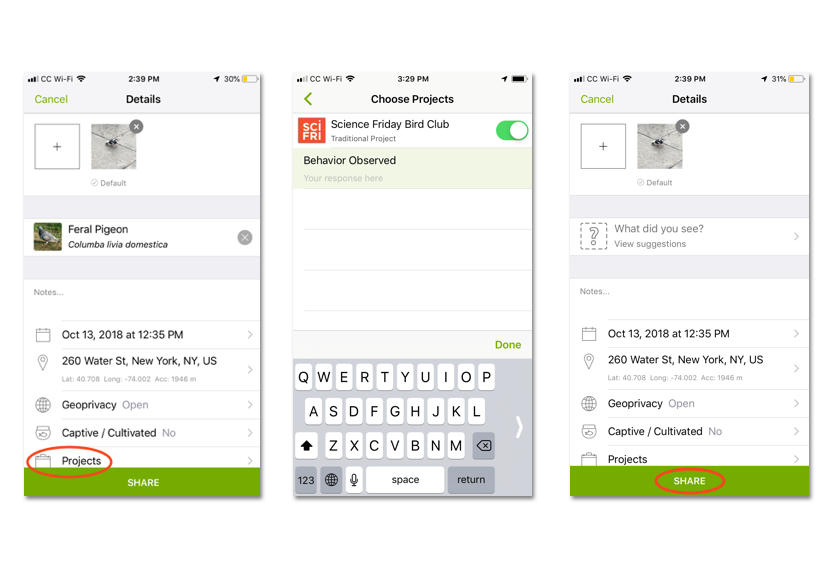

Plus, we challenge you to get outside to see your local clever birds in action! Join the Science Friday Bird Club on the citizen science platform iNaturalist. Learn and practice birding basics in an open, friendly community, and support research around the world by contributing your photos of birds. We may share your observations, comments, and even your photos on the radio show or on our website! Join the project on iNaturalist.

Martha Harbison is a birder and an editor at the National Audubon Society, based in New York, New York.

Purbita Saha is Senior Deputy Editor at Popular Science in New York, New York.

MOLLY WEBSTER: This is Science Friday. I’m Molly Webster sitting in for Ira Flatow. This summer, the Science Friday Book Club is reading Jennifer Ackerman’s The Genius of Birds, all about the many ways that birds can be brilliant, from tool-making crows to the artistic genius of bowerbirds. And it’s not too late for you to join in. Learn more at ScienceFriday.com/bookclub.

As part of the celebration, we asked you, our listeners, to share stories about birds on the new SciFri VoxPop app. That’s this app where listeners can record answers on their phones to SciFri questions. So here’s some of what you said about seeing smart bird behavior and defining animal intelligence.

MICHELLE: Here in New Zealand, we had two little blue penguins trying to make a nest under a sushi shop in Wellington City, and then waddle in the shop looking for food.

MORELIA: I think a smart animal is an animal who can reach its objective either through communicating with other animals, or figuring out a way to communicate with humans, or figuring out how to problem solve.

RONNIE: I think every kind of animal knows how to do what it needs to do. So I think that defining smartness, in a way, trying to compare apples to oranges.

GREG: Once when I was fishing, I was repeatedly whistling the theme song to The Rifleman television show. After doing it many times, I went silent. Not soon after, I heard a mockingbird repeating back the first few notes repeatedly.

[“THE RIFLEMAN” THEME SONG]

MOLLY WEBSTER: Thanks to Michelle from New Zealand, Morelia from Oregon, Ronnie from Pennsylvania, and Greg from Kentucky for sharing those stories. We want to know from you, our listeners, have you seen a bird do something surprisingly smart? Go on and tell us. Go to the SciFri VoxPop app. Find it wherever you get your apps. That’s SciFri VoxPop with a V as in Victor.

And while we’re talking about birds, we want you to go out and look at the ones near you. Whether in your backyard, you’re on the beach, you’re hiking through the woods this summer, the one great thing about birds is you can find them anywhere.

But if you’re a birding beginner like me– really never done it– or just need a few more tips, we’ve got help for you today here. With some birding one-on-one advice, here are my guest bird nerds, Martha Harbison and Purbita Saha. Both are birders and editors for the National Audubon Society here in New York. Welcome, Martha and Purbita.

MARTHA HARBISON: Hi, thank you.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Hi.

PURBITA SAHA: Hi, there.

MOLLY WEBSTER: So you guys are joining us from Wisconsin. You’re actually not in New York right now. What’s happening there?

MARTHA HARBISON: Well, this is Martha. Purbita and I are actually attending the 2019 National Audubon Convention–

MOLLY WEBSTER: Oh, that’s–

MARTHA HARBISON: –that’s put on by the National Audubon Society.

MOLLY WEBSTER: And is this like a conference of fellow bird nerds, as you describe yourselves?

MARTHA HARBISON: Yes. There are about 600 of us, actually, that have descended upon the city of Milwaukee.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Are we expecting some big, big breakthroughs? Or are we just conversing about all the types of birds?

MARTHA HARBISON: We’re talking a lot about conservation of birds, but also just like sharing the joy of them. A bunch of us have gone out birding. Pretty much the first thing I did after I dropped off my bags at the hotel room was to find a walkway along the river, and I found two juvenile Cooper’s hawks.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Oh my gosh, what does that bird look like?

MARTHA HARBISON: You see them a lot of New York City, actually. They are a mid-sized hawk, and they’re brown on their backs. And they have streaked chests and really long tails.

MOLLY WEBSTER: That’s excellent. So if you have any summer birding questions, give us a call. Our number is 844-724-8255. That’s 844-SCI-TALK. Or tweet us at @scifri. We will try and answer your birding questions. Purbita, if I go outside and I start looking at birds, is that considered birding, or is there something more that I have to do at that point?

PURBITA SAHA: No, it definitely is. Birding is just about being tapped into and aware of the many different species that surround us on the everyday. So yeah, once you go outside and you’re intentionally paying mind to the variety you’re seeing what you’re hearing, if you’re seeing scraggly little baby birds or the lustrous sleeved feathered older ones, you’re getting into birding right there.

MOLLY WEBSTER: So maybe I am a birder, and I just didn’t even know it yet. Martha–

PURBITA SAHA: Uh–

MOLLY WEBSTER: Yeah, go ahead, Purbita.

PURBITA SAHA: No, I was just going to say, I would assume millions and billions of people are, yes.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Martha, this question’s for you. So you said you landed in Wisconsin, and you immediately started to go out birding. If I’m just getting started, I don’t even know what to do first. So you landed in Wisconsin. Are you looking something up, or do you just go stand somewhere and hope you see a bird?

MARTHA HARBISON: No, I actually do a little bit of research beforehand. I mean, honestly, you can do this research even on Google Maps. I was looking for basically just little patches of green space in cities because there’ll be trees there. And therefore you’re going to be finding a lot more a variety of bird life than if it’s in a big wide field or a parking lot, for example, although you can find a lot of birds in parking lots, too.

But I also then look at– online, there’s a lot of online tools that you can use to find where other birders go, including looking up the local Audubon chapters. They usually have websites that say, this is where you go birding. Or you go to eBird, and that’s where a lot of birders log their sightings.

MOLLY WEBSTER: eBird.

MARTHA HARBISON: And they will. Yes, ebird.org. And that is run by Cornell. And that’s where you can basically pull up Milwaukee, and they’ll have all these birding hotspots. Like oh, yeah, a lot of birders go there, and they’ve seen collectively 300 species over the course of since we’ve been keeping records. So that’s going to be a really good place to find birds.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Purbita, once I find those trees, that green space, do I need to bring something with me, or do I just go?

PURBITA SAHA: Yeah, ideally, you would have a pair of binoculars. A solid pair can range from $200 to much higher if you want to get fancy. But it can be, especially now in summer when the trees are leafed out, it can be kind of frustrating to get your sights on a specific bird. So the binoculars will really help you hone your focus and obviously increase your visual quality times, like, 10.

But yeah, binoculars is really kind of the staple. If you can take along a field guide, it can be a paper guide, or it could be– there are a variety of digital apps now. Audubon has a free one that has hundreds of birds and their calls. Cornell and Sibley– they’re a great variety to choose from.

So those are really the two key tools, but also sometimes you’ll get stuck without binoculars, without a field guide, and you can still go birding. So it’s really not ride or die.

MOLLY WEBSTER: OK. So we have a question for you guys from Terry on Twitter who says, why are robins so successful, and why aren’t indigo buntings, or scarlet tanagers, or grosbeaks, or belted kingfishers? So why do the robins reign supreme?

MARTHA HARBISON: That’s an excellent question. I think– and Purvita, feel free to chime in here– but I think it has to do, among other things, with habitat. Robins can thrive in a lot of different areas, whether it’s in a city park, or if it’s out in the suburbs, or in rural areas, whereas indigo buntings and scarlet tanagers have much more rigorous habitat requirements, especially when they’re breeding.

So they’ll only want to nest in one type of tree. Or indigo buntings really love to sit on the top of trees and shrubs. So if you don’t have those around, then they’re not going to hang around. And so I think it has to– basically, robins are just a little bit more flexible than the other two that were mentioned.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Hm. What about if I find a nest of birds? What I always grew up hearing was if you find a nest, don’t touch it, or if you find a baby bird, don’t touch it because the mom will abandon it or the nest. Is that true, Martha?

MARTHA HARBISON: Yes and no. If you find a nest, don’t disturb it, and keep your distance from it. But there’s actually a lot of nuance in– it’s like if you touch a bird, it’s not really true that the parent is not going to– that the parent will abandon it. There are some species that do that. But for the bird that you’re typically going to run across like a robin, they don’t care that much.

But and where the nuance comes in is that if you find a baby bird, if it’s a really tiny one that hasn’t had feathers, then yes, you probably want to intervene because it’s not going to survive. Basically pick it up, try and find the nest to put it back in. Or take it to the Wild Bird Front, which is a rehab place in New York City.

But if it’s like kind of a scraggly looking bird– maybe it’s got some feathers, and it’s just looking a little confused– that’s probably a fledgling, and it’s learning how to fly. And so you should just leave it alone, because that’s part of its lifecycle.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Purbita, you guys are in Wisconsin right now. You want to go out birding. Is there a difference with birding in the summertime as opposed to– I think of July as like a very lazy time. Is there a difference with summer versus other times of the year for birding?

PURBITA SAHA: Yeah, I mean, there’s a big switch in just which birds are available. We’re not in migration season now, so we’re limited to any birds that would be what we call resident species in our area. And at the moment, they’ll either be nesting, or taking care of just fledged chicks, or even just gearing up for fall migration. So largely the songbirds might be laying low. You can still hear some of them calling. Some common species like gray catbirds and gold finches, they’ll keep singing all summer long.

But otherwise, shore birds are really, really abundant at the moment. If you live along the west or east coast and you go to your local beach, you might see some nesting plovers, or yeah, they’re really fun. They’re spunky. They love to run across the beach, turns diving on the water. So shore bird habitat is where it’s at during the summer.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Martha, do you have any favorite summer birds you’re looking for?

MARTHA HARBISON: This is like a cop-out– I love all summer birds. [LAUGHS] I love the surly teenage birds. They’ve just come out of the nest. And they’re sitting on branches, and they’re yelling at their parents to get fed and flapping their wings a lot. So it doesn’t matter what species it is. I’m always charmed. Like, house sparrows rolling around on the ground, that’s perfect.

But in the summertime, yeah, like Purbita said, I actually really love American oyster catchers. They’re these very charismatic shore birds that have huge orange bills, and they’re black and white otherwise. And they’re always running along the shore and trying to pull up crabs.

MOLLY WEBSTER: That’s so wonderful. I’m Molly Webster, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re here talking about birding with Martha Harbison and Purbita Saha, who are in Wisconsin, ready to go birding. I’d like to take a call right now from Bobby from St. Cloud, Minnesota, who wants to ask about identifying some birds. Bobby, are you there?

BOBBY: Yeah, this is me. I’m in the St. Cloud area, so not too far from you guys in Wisconsin. I was just wondering about a bird that I saw yesterday while I was walking my dog. Actually, it was a pair of them. And they looked like– I mean, I assume that they were a native pair because they were sitting on a wire, actually, right next to each other.

But I’ve never seen so much of a difference between two birds. I’m assuming it was based on gender. But one of them was roughly pigeon sized, and it was totally white. So I assume that was some kind of dove. And the one next to it was maybe about 3/4, even half the size, and was mostly blackish gray with a few spots of white around it. And I didn’t have my phone with me so I couldn’t get a good picture of it, unfortunately.

I have the Cornell bird identification app on my phone, and I tried plugging in some of the characteristics as far as where I was when I saw it and everything. But I was just wondering if you had any idea on what that might be.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Purbita, does that sound familiar?

PURBITA SAHA: I mean if your first impression was that it was a pigeon, well, pigeons and doves have a very distinct shape where it kind of looks like they’re headless almost. They have pinheads. So and just the variation you’re describing in the feathers makes me think it is a pigeon, just because even if they’re the same species, you’ll see a lot of variety in how they’re bred and what their plumages look like.

I’m not so sure about the size difference. That might just have been the way the birds were postured. But yeah, I can’t really think of what other options there might be. But you’re completely right. Between sexes in the species, depending on the species, you could get a lot of variation in how the bird looks, how it’s sized. So the technical term for that is sexual dimorphism. But yeah, Martha, what do you think?

MARTHA HARBISON: I was thinking the same thing as you, that if it reminds you of a pigeon, it’s very likely going to be a pigeon. And there is such a broad range of plumages in the pigeon family, especially when it comes to the feral rock pigeon. That would be my first guess. And again, I’m not sure what to make of the size difference because you don’t see huge sized dimorphism in most bird species. There are some, but it’s fairly rare. So it could just be a postural thing.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Awesome. Well, we are out of time. Thank you so much, Martha Harbison and Purbita Saha, birders and editors at the National Audubon Society in New York. Thank you for joining us. Now that you’ve got some birding 101 basics, it’s time for everyone out there to go outside. You can join me and the rest of Science Friday at the Science Friday Bird Club on the Citizen Science platform iNaturalist.

And whether you’re a veteran birder or you’ve never picked up a pair of binoculars, it’s a really collaborative Citizen Science community that you can be a part of, and just kind of geek out, and have fun. We’re also collecting photos of birds. So you can tell us where you saw them and snap what they look like. And all of this can actually help research and science all around the world. So learn more about the Science Friday Bird Club at ScienceFriday.com/birds.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

Molly Webster is a producer and guest host of WNYC’s Radiolab in New York, New York.