The Art And History Shaped By Volcanic Winters

Volcanoes have a long and storied history of altering the course of human culture.

This story is part of our winter Book Club conversation about N.K. Jemisin’s book ‘The Fifth Season.’ Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or send a voice memo to voices@sciencefriday.com.

This story is part of our winter Book Club conversation about N.K. Jemisin’s book ‘The Fifth Season.’ Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or send a voice memo to voices@sciencefriday.com.

The immediate effects of a massive volcanic eruption can be often hot and violent, with scorching lava streaming from the caldera and volcanic rock launching into the air. But after the activity subsides, the effects of the eruption can echo through the air for months to years—ash, soot, sulfurous gases, phosphates, and other chemicals stir changes in atmospheric chemistry.

“You think about aerosols being launched up into the stratosphere, they’re going to move,” says Jennifer Marlon, a research scientist at Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. “They’re going to swirl around the planet, essentially, and affect distant continents in some cases.”

The aerosols block radiation from the sun, creating a cooling effect known as volcanic winter. This climate-altering period can ripple throughout history, both in the short and long term, says Jessica Whiteside, a geochemist and paleoclimatologist at the University of Southampton. A volcano erupts thousands of miles away, and a river in Africa ceases to flood, for instance. In Indonesia, volcanic ash spews in the air, casting a dreary, dark storm across the summer—and creating the perfect backdrop for a science fiction novel. The subsequent years after an eruption can awaken “a creative side because the red skies from the aerosols in the atmosphere lead to works of [J. M. W.] Turner and Edvard Munch,” Whiteside says. “But the longer term consequences are linked to epidemics.”

Discover how volcanic winters have colored famous works of arts, shaped societies, and influenced culture.

For the ancient Egyptians, water was life. And if for some reason the Nile didn’t flood, trouble would brew. No flooding meant no harvest, and no harvest meant social and economic volatility, such as revolts against the ruling class and families offloading their land because they couldn’t produce enough crop yields to pay taxes. But sometimes, the source of these Nile troubles came from halfway across the planet..

By comparing sulphate and ash deposits locked inside from ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica to meticulous historical records from Ptolemaic Egypt (305-30 BCE), a team of historians and scientists have connected certain years of drought and Nile suppression to a series of volcanic eruptions from up to thousands of miles away—and they argue that the eruptions likely triggered riots and social unrest.

Integrating natural and human records wouldn’t have worked just anywhere. Ptolemaic Egypt was the first period in Egyptian history for which well-documented records still survive. Researchers studied two sets of records. First, they looked at records of Nile flood heights, from nilometer readings and written, anecdotal evidence like letters and even graffiti. Then, they examined official documents that held clues of social unrest, like missing tax receipts or the issuance of priestly decrees that were intended to maintain order. Taken together, the records piece together a timeline of Nile drought and its social consequences.

Meanwhile, the ice cores carry traces of dozens of volcanic eruptions during the Ptolemaic period from as far away as Alaska and Indonesia. As aerosols from the eruptions traveled around the world and volcanic winter settled in, temperatures at the surface fell, and evaporation from oceans and large bodies of water were also reduced. That led to less rainfall in Africa, which led to Nile flow failure.

Using the ice cores and written records, researchers synced some periods of social unrest in Ptolemaic Egypt to years of drought, and years of drought to distant eruptions.

“That’s why having a long, continuous historical record coupled with a long, continuous ice core record is so critical to this study,” says Marlon. “Any time you want to study the cause of an extreme event, it’s a difficult question because you need to look at dozens of them… they are by definition rare events.”

Still, the researchers caution against viewing the results of the study as “environmental determinism.” These eruptions and subsequent events were happening against a backdrop of other stressors in Ptolemaic Egypt—ethnic tensions ran high between the Egyptians and Greek elites, and heavy state taxation and the cost of military mobilizations burdened the ancient Egyptians financially. The powder keg was set, and the eruptions were the spark.

Iceland’s celebrated medieval poem, Vǫluspá, depicts an apocalyptic scene: “The sun starts to turn black;” “…venom-drops [flow] in through the roof-holes;” “…flame flies high against heaven itself.” All this sets the stage for the “fiery terminus of the pagan gods” and the “coming of a new (and singular) god.” Now, researchers have linked the events in the poem to a major volcanic eruption—and they argue that it played a role in Iceland’s conversion from paganism to Christianity.

Researchers believe that the poem is referring to the Eldgjá eruption, which they say is the largest volcanic eruption of the Common Era in Iceland. It ejected roughly 19.6 cubic kilometers of lava across the ground and spewed plumes of sulphur dioxide into the air. But for centuries, researchers weren’t able to peg the date of the eruption, making it tough to draw conclusions about its social and cultural consequences.

To pin down the date, researchers investigated ice cores and tree ring data. They unearthed an ice core from Greenland that carried traces from both the Eldgjá eruption and a different volcanic event whose date was already known. With this time stamp, researchers determined that the Eldgjá eruption began in spring 939 CE. In addition, tree ring-based reconstructions revealed a cooling effect reminiscent of volcanic winter in the summer following the eruption.

The newly-dated eruption, which occurred a little more than 20 years before the epic poem Vǫluspá was composed in 961, shed new light on some of those details. Those “venom-drops” were likely acid rain, which is associated with volcanic plumes, and references to the leaping flames and fire are interpreted as first-person accounts of the effects of the Eldgjá eruption. As for descriptions of the sun blotted out by darkness, Sigurður Nordal, an Icelandic medievalist Sigurður Nordal, who edited the poem, wrote in 1923: “I do not think I have ever understood this description until I saw volcanic ash falling in a clear sky from the eruption of Katla in 1918. The sun was shining then, but it was dark, as was all its shine. Impressive as a total eclipse of the sun is (as popular beliefs and folktales witness), this was yet much more grim and terrible.”

The researchers argue that drawing upon the harrowing events of the Eldgjá eruption—and the emergence of a new god—was an intentional nudge towards Iceland’s conversion to Christianity over the second half of the 10th century, the following two generations after the Eldgjá eruption. (Iceland’s formal conversion to Christianity dates to 999-1000 CE, which falls within two generations of the Eldgjá eruption.) “In calling attention to experiences and memories of the Eldgjá eruption as signs that the old pagan ways were doomed,” write the researchers, “Vǫluspá suggests that the eruption acted as a catalyst for the profound cultural change brought about by conversion to Christianity.”

In 1783 to 1784, a thick veil of volcanic ash cast a shadow over much of the northern hemisphere. South of Iceland, the fissure Laki erupted for eight months, spewing millions of tons of gasses into the atmosphere and forming what locals in Iceland called the “Haze Famine.” The noxious chemicals were taken in by grasses and vegetation, crippling crops and poisoning grazing livestock, of which 60 percent died. In Iceland, over 10,000 people were killed from famine and disease.

The deathly haze was witnessed as far away as China and North America. For two to three years after Laki’s eruption, northern hemisphere temperatures stayed 1.3ºC below normal, while sulfur in the atmosphere precipitated down as acid rain and fog. French records and newspapers noted that the fog created a light tint the color of “a dry leaf” and that the sun blazed red as if one looked at it through “a smoked glass.” The “dry fog” crept into Europe and plunged France into a bitter winter, as America’s then-ambassador to France Benjamin Franklin observed from Paris in the summer of 1783:

While he had incorrectly associated it with another Icelandic volcano, Hekla, one of Franklin’s hypotheses had been that the fog originated from volcanic emissions.

In the summer of 1783, the volcanic fog that settled over Europe created strange weather patterns, withered crops, and worsened human health, John Grattan and Robin Torrence write in the book Living Under the Shadow: Cultural Impacts of Volcanic Eruptions. France experienced an uptick in mortality rates, and more reported air pollution induced illness and death, which researchers publishing in Comptes rendus Geoscience tie with the Laki’s eruption. All these repercussions from the bitter cold piled on top of France’s social unrest as the country teetered on the brink of a rebellion.

“Those crop failures across the north hemisphere played a critical role in the [1789] French Revolution,” says Whiteside. “The famines that were known in France, it wasn’t just the mismanagement of funds, but it was actually caused by [volcanic] winters.”

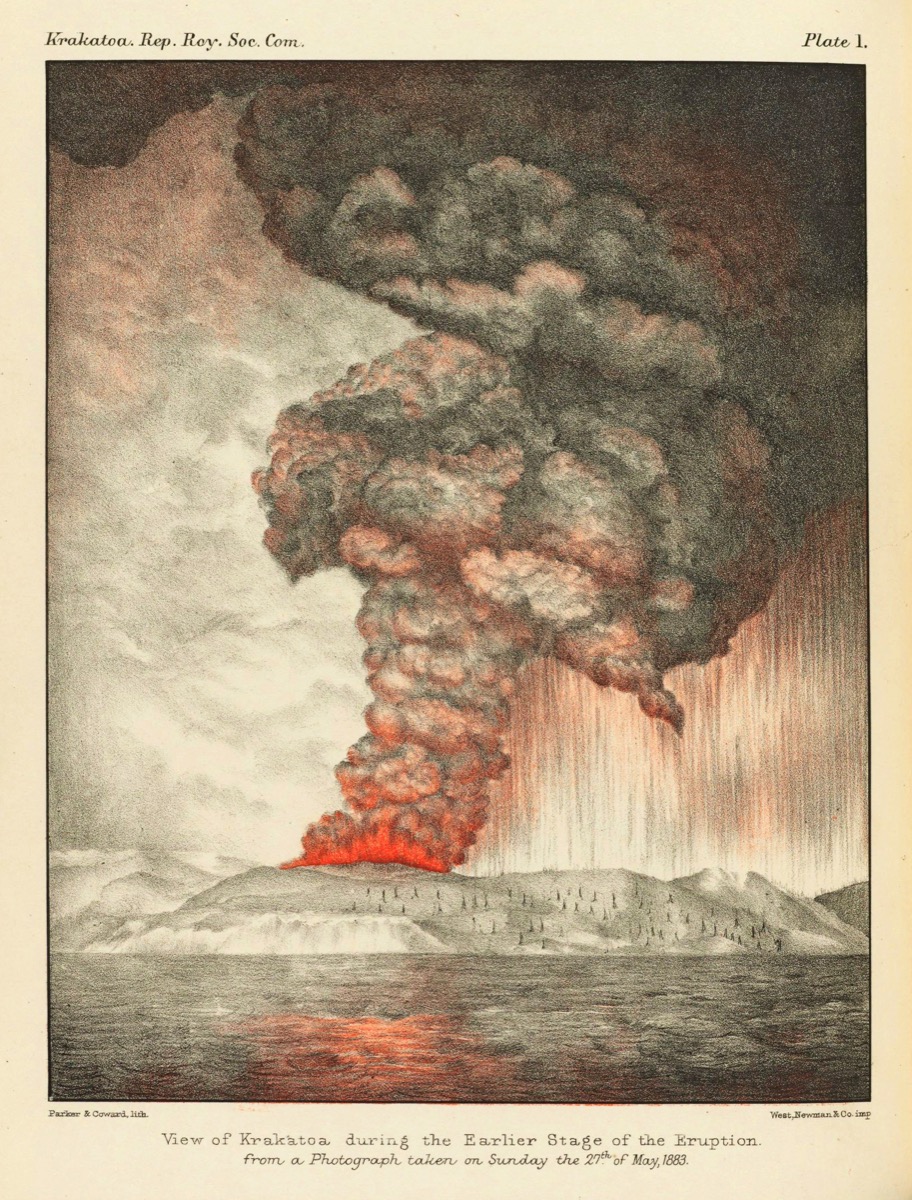

In 1815, a monster awoke. Mount Tambora, the stratovolcano in Indonesia, unleashed a torrential fury. The massive volcanic event killed 92,000 in the immediate aftermath of the eruption, but the repercussions were even larger.

“The largest eruption that we’ve seen in the last 500 years was Tambora in 1815,” Whiteside says. One hundred cubic kilometers of ash was ejected from the mountain, which would “cover New York City in 650 feet of ash.”

The massive amount of aerosols and ash ejected in the air reduced hemispheric average temperatures by 0.7°C , and turned 1816 into the “Year Without a Summer.” As temperatures dropped, famine and epidemics ensued. “It’s thought that since there’s such a change in climate that it actually allows some diseases to proliferate further than they normally would because the climate envelopes have shifted,” she says. “Subsequently, millions of people were killed because of the spread of typhus.”

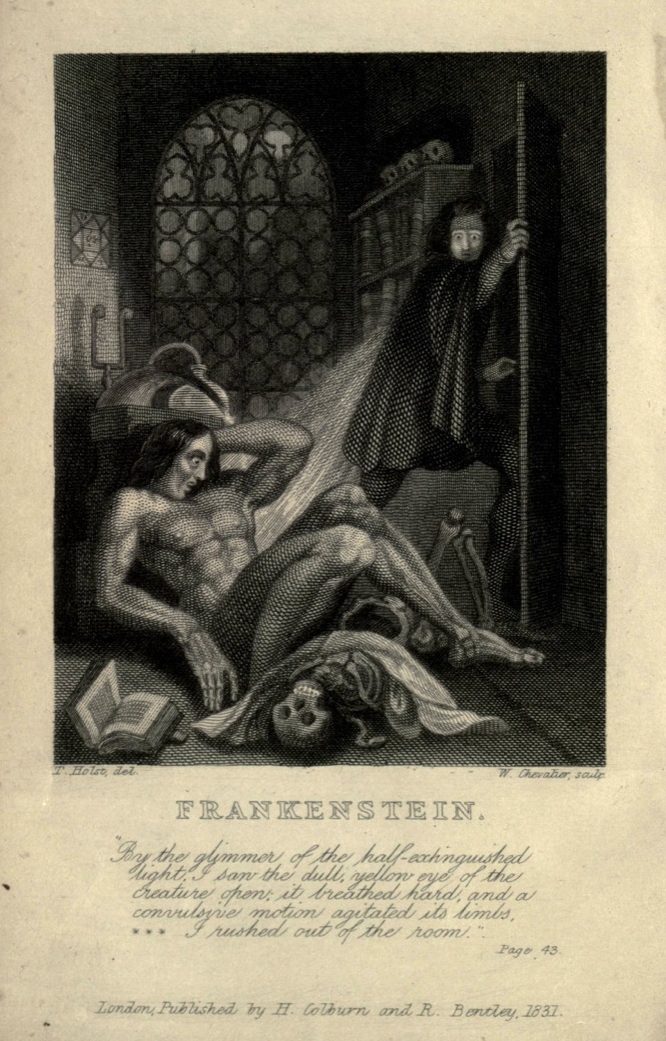

During that cold, wet summer of 1816, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and her literary circle were sequestered indoors in Geneva.

“An almost perpetual rain confines us principally to the house,” Shelley wrote in letter in June, 1816 while staying at Lake Geneva. “One night we enjoyed [emphasis in text] a finer storm than I had ever beheld. The lake was lit up—the pines on Jura [a nearby mountain range] made visible, and all the scene illuminated for an instant, when a pitchy blackness succeeded, and the thunder came in frightful bursts over our heads, amid the darkness.”

From the ashy chill of a monstrous volcanic winter, the monster of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was born, explains Whiteside. Thunderstorms and winter played a thematic role—descriptions akin to her letters from the summer of 1816 snuck its way into Shelley’s novel, as Bill Phillips points out in the journal Atlantis, such as in the scene after Victor Frankenstein creates the monster:

“There was a literal and metaphorical spark from the unusual winters of that time and also because incidentally there was an Italian scientist… that showed that electricity could cause the muscles of a dead frog to twitch,” Whiteside says. “She put all of that together and emerged Frankenstein.”

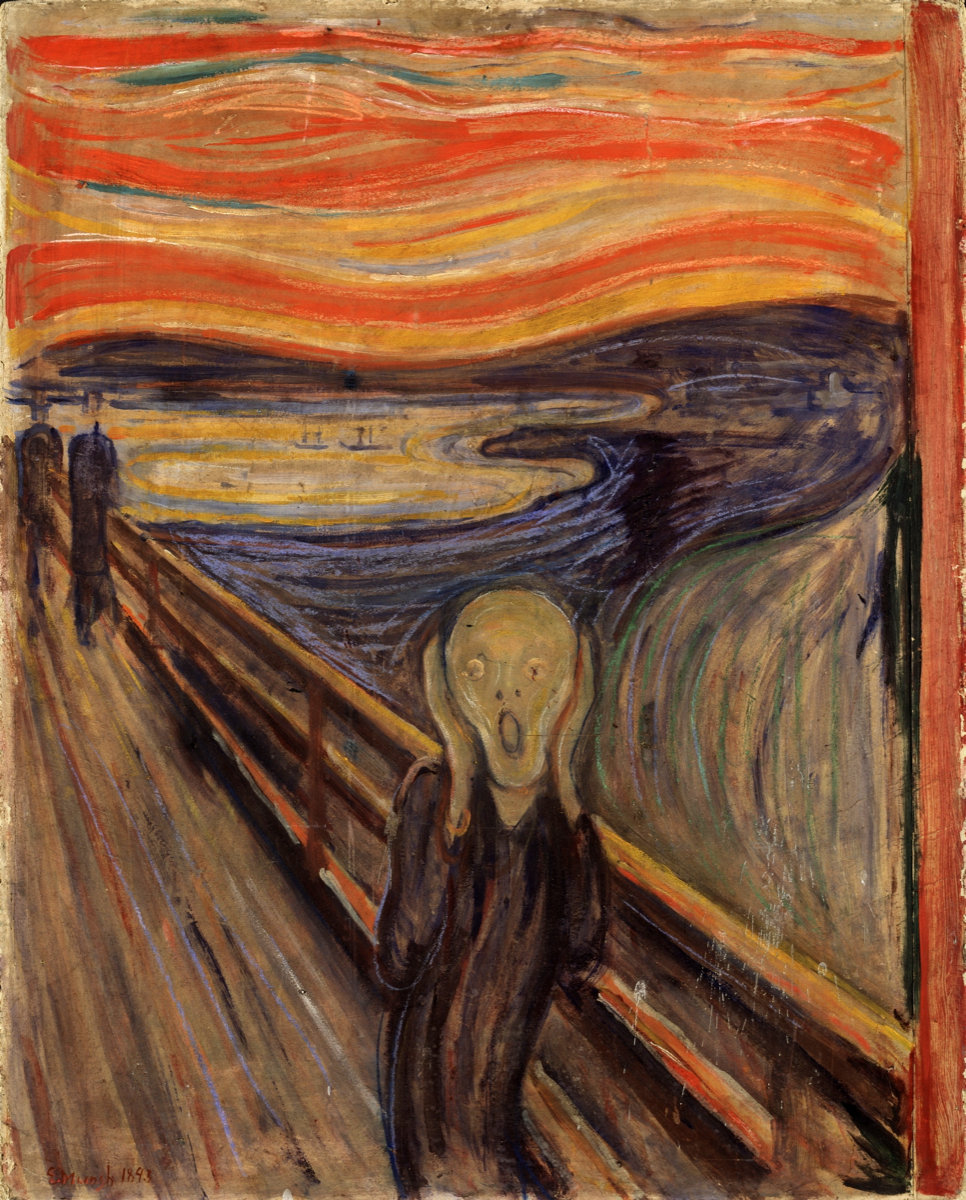

When Krakatoa erupted in 1883 in Indonesia, Norwegian artist Edvard Munch was out walking with his friends. As he watched the sun sink into the horizon, the scene transformed into one of horror.

“Suddenly the sky turned blood red,” Munch wrote in his journal a decade later, in 1892. “There was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city—my friends walked on, and I stood alone, trembling with anxiety. I felt a great, unending scream piercing through nature.”

A year after recounting in his journal, he painted his most iconic version of “The Scream.”

“After Krakatoa, it was another one of these instances where there were unusual and prolonged sunsets,” explains Whiteside.

The orange and red “tongues of fire” that swipe across “The Scream,” are believed to be a result of the dust and gases that were ejected into the atmosphere from the peak of Krakatoa’s explosion, according to researchers Donald Olson, Russell Doescher, and Marilynn Olson, who wrote about their analysis of Munch’s journals and painting in Sky and Telescope. The researchers reviewed meteorological reports and newspaper articles about twilight glows in November 1883 and February 1884 in Norway and pinpointed the location where Munch had reportedly been in Oslo.

“Munch’s own words, along with our topographic results, provide strong evidence that these blood-red afterglows are the connection between one of the world’s most famous volcanoes and one of the world’s most famous paintings,” the researchers wrote.

A separate study published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics in 2007 evaluated the color changes of a variety of famous sunset paintings created between 1500 and 1900—a time period containing 11 major volcanic eruptions, including Krakatoa—to estimate historic volcanic dust levels. In addition to their official sample, they did an analysis on “The Scream” and found optical coloration evidence that suggests Munch witnessed the scene after the Krakatoa eruption.

“I just find it beautiful,” Whiteside says. “The fact that climate has the subconscious influence on visual art and actually drives moments in literary work as well.”

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.